Exploring DEI Strategy at a Consumer-Owned Food Cooperative

In my hometown of Ithaca, New York, GreenStar has been, for many, a symbol and a center of ethical food retail since its birth in the early 1970s. When its Bylaws were first written in 1971, the GreenStar operation consisted of Ithaca volunteers driving the 56 miles to Syracuse and back every Saturday morning, transporting healthy and local farm food which they pre-ordered and distributed to community members at just 5% wholesale mark-up.

Today, the consumer-owned grocery cooperative boasts three stores across the city, servicing 12,000 member-owners and thousands of non-members who are also free to shop.

Like many food cooperatives which sprouted from affluent, liberal, and predominantly white communities in the 1970s and 80s, racial equity and inclusion have not always been priorities for the cooperative. In fact, goals of diversity and affordability have, in some ways, historically cut against GreenStar’s founding vision, which emphasized stringent guidelines for the quality and nature of which products were fit to sell (for example, members only voted to begin selling meat in 2002). The stocking and pricing decisions of the cooperative relied heavily on standards of ethical eating, without too much explicit concern for the inclusion of community members with different food preferences and socioeconomic statuses.

This isn’t too surprising. Consumer co-ops, at their origins, consist of a group of people who join together to procure some product for themselves– which they all want and intend to purchase regardless– at lower costs, financial and otherwise. The impulse for creating a consumer cooperative is one of exclusivity. It signals– it is– a fencing off of a community of consumption, generating solidarity in shared preferences and savings for members.

Andrew Zitcer, in his 2014 article “Food Co-ops and the Paradox of Exclusivity,” writes that “consumer food co-ops wrestle with a paradox of exclusivity, whereby some practices and people are inadvertently left out in order to create conditions for a strong identification among others with particular ways of being and going.”

He goes on to elaborate that the paradox “frequently plays out in the exclusion of people of color, those who cannot afford the co-ops’ prices, and those who are alienated by the co-op’s food selection or organizational practices.”

Like any business, whether conventionally- or cooperatively-owned, the mandate for growth forces continual and creative expansion: into new storefronts, which the cooperative achieved in 2020, but also into new communities of members and new ideologies of self-recognition. Whereas once GreenStar was a small group of like-minded, personally-engaged, and relatively well-off individuals who had the time and means to drive to Syracuse to source organic food, today it strives to be a competitive supermarket that’s appealing and accessible to every Ithacan. GreenStar wants to be a cooperative where membership is both achievable and desirable for everyone who lives within driving radius, and who seeks a means of food access that offers healthy options, a sense of community, and a democratic voice in how food is sourced and sold.

How has GreenStar evolved to expand its social and cultural footprint? And to what extent has it been successful in welcoming new segments of Ithacan shoppers into meaningful belonging in its community?

DEI in the Membership

The only requirement to be a member-owner of GreenStar is to make a one-time equity purchase of $90, and the co-op offers payment plans starting at $5/month. But there are many other considerations that contribute to an individual’s decision of whether to join the ranks of a food co-op’s membership, in addition to the financial burden of an equity purchase.

The approach rests on affordability, so that more Ithaca and Tompkins County residents are able to shop at GreenStar; product diversity, so that more residents actually want to shop at GreenStar; and finally, on inclusive governance, which will hopefully encourage new shoppers to become members and eventually help shape the direction of the co-op by actively participating in member-governance.

Affordability

Affordability is the first and often the toughest barrier to inclusivity at food cooperatives, because many folks automatically assume that grocery co-ops will be more expensive than chain supermarkets. While it’s difficult to find robust data that confirms or denies this suspicion on a national level, even the perception of high prices, regardless of actual numbers at the register, can create the problem of exclusivity.

At GreenStar, a radical thrust for affordability– to tackle both the perception of high prices, and price barriers themselves– came about 12 years ago, with the implementation of the FLOWER (“Fresh, Local, and Organic Within Everyone’s Reach”) program. This program offers a 13% discount for shoppers who benefit from any official government affordability program. It’s expansive: eligible beneficiaries include EBT cardholders, (who can access discounted foods at most stores selling food products), but extends further, to include enrollees in Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), Medicaid, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), and Pell Grant-holders, among others.

Participation in the FLOWER program is also open to shoppers who are not yet co-op members; approved FLOWER applicants will receive a trial one-year membership. In this way, the FLOWER program is not only a means of reducing cost burden for low-income, loan-holding, and otherwise financially-disadvantaged members, but also of inviting financially-disadvantaged community members into the co-op in the first place.

Like many cooperatives, GreenStar has also formalized an infrastructure for mutual aid, allowing members to collectively subsidize fellow-members in need. That’s the Solidarity Fund, a revolving fund of indivisible co-op equity which covers the costs of gaining and maintaining membership for FLOWER-eligible shoppers. Members can pay into the Solidarity Fund by contributing above the minimum required equity.

But Marilyn Chase, GreenStar Council President, cautions against equating financial subsidies with “achieving” diversity, equity, and inclusion. While lowering cost barriers to membership is a crucial element to DEI, it’s not always sufficient to attract and include new members in ways that are sustainable and enriching to both the member and the co-op.

Product diversity

Another important way to foster a truly welcoming shopping environment for new members is to actually carry the foods that they want to buy. Home to both Cornell University and Ithaca College, Ithaca is a particularly transitory and international community, exposed to demographic shifts, especially among college students. GreenStar leadership has begun asking itself: Who are we serving, and who are we not serving?

Without the resources to conduct rigorously and culturally-focused market research, co-op decision-makers rely on pre-existing connections and in-store community-based surveying to understand the gaps in their servicing. For example, noticing the rising numbers of Asian students attending Cornell, Jeff Bessmer, GreenStar’s General Manager, decided to reach out to the National Cooperative Grocers’ Association to request a written list of must-have products in Asian groceries’ inventories.

In-store, the cooperative also recently instituted a survey at checkout, which randomly requests feedback from 5% of shoppers (in exchange for a coupon); the idea is to cull the response bias that taints data when only a small sliver of unusually upset members take the time to offer feedback. The survey spits back revelations: “How do you not have kimchi???”

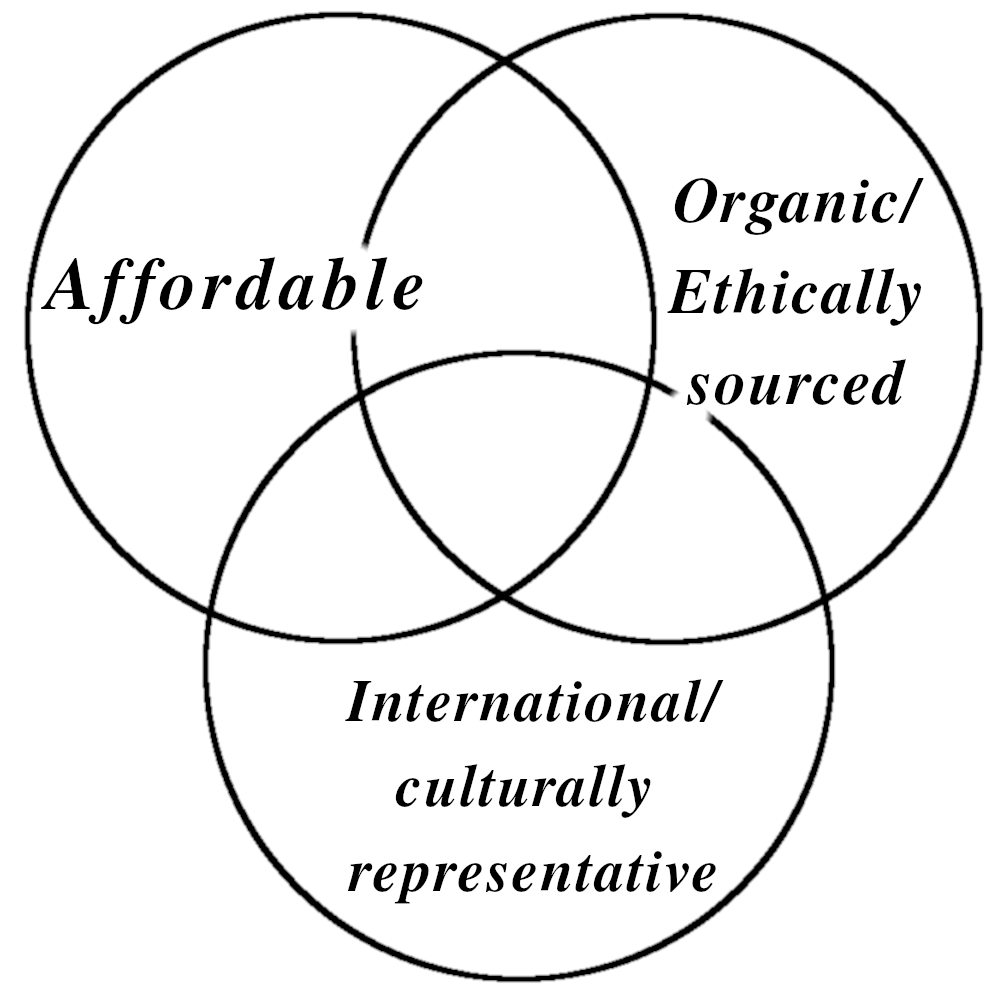

In some ways, GreenStar’s recent attempts at diversifying product stock have overlapped with efforts towards affordability: for every project, the co-op tries to stock one higher-quality, more expensive version, and a second, lesser-quality, less expensive version. In other aspects, though, seeking less common and more globally-representative foods complicates GreenStar’s preference for providing the best-of-both-worlds between affordability and quality. It’s difficult enough to find suppliers who offer sustainably-sourced products at reasonable prices, but even tougher to patronize authentically representative businesses, whose products are the-real-deal and who are actually owned by people from the cultural demographic they profess to represent.

Chase reflected on the perspective she often encounters when discussing food cooperatives with friends and neighbors who are surprised to find, say, nonorganic produce on the shelves: “I thought a co-op was supposed to carry fair trade/organic/local foods?!” That’s the goal, Chase says, but it shouldn’t necessarily come at the expense of other desirable qualities like affordability and cultural diversity. With ever-globalizing supply chains and the ever-globalizing Ithaca community, products that meet those high ethical and health standards don’t always cover the market demand from Ithacans, and reasonably-priced suppliers of desired products don’t always meet high ethical and health standards.

And attention to cultural inclusivity remains crucial once the jars of kimchi are already ordered, invoiced, and carried from the truck into the store. Where do they go? To an “Asian Foods” aisle with the rice noodles and soy sauce, or integrated with other pickled and jarred products that might serve similar functions to kimchi in a recipe? When he was at Sacaramento National Foods Co-op, Bessmer led a floor-redesign to integrate international food aisles onto shelves with all other products. Bessmer believes that international food aisles and other culturally-based segregation of products can be othering to shoppers who buy these items, actually cutting against the atmosphere of inclusivity that might be created by carrying such products to begin with.

Inclusive governance

The last prong of diversity, equity, and inclusivity strategy takes place on the plane of governance, to ensure that once diverse shoppers have entered the doors of the co-op and joined the ranks of the membership, they are equipped and encouraged to take part in governing the company, which is the central and sacred privilege of cooperative members. Establishing inclusive governance is in fact the only reliable way to sustain inclusivity, because it politically empowers diverse interests to protect and promote themselves, all the way down through the full infrastructure of organizational decision-making.

The core vision of democracy– a constantly-tested assumption– is its tendency for self-preservation: absent external, non-democratic forces, we hope that democracy re-elects itself. In the same way, there is the assumption that diverse voices, when empowered, will defend, uplift, and sustain the empowerment of diverse voices.

One of GreenStar’s tactics to strengthen inclusive governance has been to revisit its Bylaws, which, like most organizational bylaws, express the rights and responsibilities of the membership in non-vernacular legal terminology. Chase thinks it’s important that the language of the bylaws makes sense to any person who speaks English, even those for whom English is a second or third language.

There are many organizations that support cooperatives in this effort, including the Consumer Cooperative Management Association. Chase also mentioned Weaver Street Co-op, a North Carolina-based grocery cooperative, as a model for inclusivity. GreenStar is in touch with Weaver Street to understand best practices for inclusive governance– another great example of the 6th Cooperative Principle: cooperation among cooperatives.

A scorecard?

There are many ways to assess the DEI success of a cooperative, and demographic data is only one, very limited dimension. To understand how well GreenStar is doing at representing and welcoming the whole spectrum of Ithaca and Tompkins County community members, you’d have to talk with many of those people, both GreenStar members and nonmembers.

And, regardless, conforming to a common shortcoming, the GreenStar leaders with whom I spoke did not have demographic data on hand. (Attempts to speak with a current member or worker were unsuccessful.) According to the University of Wisconsin Center for Cooperatives’ 2021 Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Trends in the Cooperative Community report, only 24% of cooperatives (not specific to food co-ops) track membership demographic data, and 8% of food co-ops publish their demographic data, an elite minority to which GreenStar does not belong.

Although GreenStar didn’t share specific numbers, Bessmer did tell me that the racial demographics of the staff reflects the racial diversity of Tompkins County where GreenStar is located. However, the membership is “more” white than the surrounding area.

Returning to Chase’s phrasing, diversity, equity, and inclusion are not things that can be “achieved”, but only practiced, and pursued. Numbers will never tell a story of success, a case closed. As GreenStar blooms bigger and taller into the twenty-first century, its task may be a never-ending and doubly-challenging effort: to not only hold up its original goals– to be at once a warm community, a source of ethical and healthy food, and a democratic politic– but to expand how far those goals reach: into new neighborhoods, tackling new brands of skepticism, and making new allowances for how goals-at-odds can be balanced in this ever-changing world.

Bibliography

Chaisson, B. “Grain Store to GreenStar: The cooperative celebrates 50 years”. Ithaca.com. 2021 December 9. https://www.ithaca.com/news/ithaca/grain-store-to-greenstar-the-cooperative-celebrates-50-years/article_a375bbb8-5944-11ec-bb42-f748bfdc0200.html

Schlachter, L. H. Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Trends in the Cooperative Community. University of Wisconsin Center for Cooperatives. November 2021. https://ncbaclusa.coop/content/uploads/2021/11/DEI-Survey-Report-11-10-21.pdf

Zitcer, A. (2015), Food Co-ops and the Paradox of Exclusivity. Antipode, 47, 812– 828. doi: 10.1111/anti.12129. https://www.ithaca.com/news/ithaca/grain-store-to-greenstar-the-cooperative-celebrates-50-years/article_a375bbb8-5944-11ec-bb42-f748bfdc0200.html

Header image via GreenStar Food Co-op's Facebook page.

Citations

Emma Karnes (2023). A GreenStar For All: Exploring DEI Strategy at a Consumer-Owned Food Cooperative. Grassroots Economic Organizing (GEO). https://geo.coop/articles/greenstar-all

Add new comment