Amsterdam's Sharing Economy Action Plan

cross-posted from Shareable

cross-posted from Shareable

It's undeniable that major sharing economy services are changing the landscape of many cities around world. Governments are scrambling for regulatory solutions to address how these platforms impact their communities, but it's been a thorny process. This is due to the fact that the sharing economy creates a range of winners and losers, all of whom have a great stake in how these services are organized and regulated. Ultimately, you can't foresee how sharing economy services impact people's lives until you look at whose interests they're specifically designed to benefit — community members, workers, or shareholders?

As a sharing city, Amsterdam has been one of the most proactive cities to address such the impacts of the sharing economy head-on. Ahead of a Sharing City event held in the city at the end of May, Amsterdam released its action plan. This action plan demonstrates a pragmatic approach to deal with the sharing economy. However, Amsterdam also manages to avoid raising questions about the true benefactors of the sharing economy, and how the organizational objectives and governance structure behind any given sharing enterprise is critical to understanding how they will relate to and impact the community of people who participate in their initiative.

The report recognizes that what's most important is analyzing these sharing services' direct impact on the city's inhabitants and highlights the current opportunities and challenges. Some of the opportunities include how these platforms can enable people to share scarce resources more effectively and sustainably, increase social engagement and enhance social cohesion and safety, and allow people to have cheaper and easier access to goods and services. On the other hand, they also acknowledge challenges — such as how they may exacerbate income inequality, become a public nuisance, create greater power imbalance, or risk becoming a monopolistic industry. The report includes a process wheel and checklist of questions to help guide cities in their evaluation of platform services.

In order to bolster the good and mitigate the bad, Amsterdam's action plan takes a pragmatic approach to collaborate with these services through its five-point strategy.

Their first phase is to stimulate the sharing economy by enabling collaboration between stakeholders and supporting new pilot projects that help tackle existing urban challenges. Second, Amsterdam plans to lead by example by launching its own pilot project of sharing city assets like its vehicle fleet and office space, free to the public. The third is to ensure that these initiatives are inclusive to all local residents through public-private partnerships, such as connecting sharing platforms with the existing city pass system and setting up public education programs. Fourth, Amsterdam plans to craft rules that remove regulatory barriers for the sharing economy that also protect the public interest. Then the final piece of their approach is to make their work as a Sharing City more widely visible by participating in global events. The aforementioned Sharing City Event that took place in Amsterdam was one of the first such events, and it was attended by 12 other cities.

The most well-known players in the sharing economy are multinational corporations that make underutilized goods and services available — largely through Internet-enabled platforms — and directly connect supply to demand. Other, perhaps more accurate, terms have been coined to describe this, such as the "gig economy" and "on-demand economy." But the rhetoric of sharing has been predominant, and the general perplexity around what these terms mean have also affected people's ability to have an honest conversation about how to deal with the consequences arising from this phenomenon.

That's why shareNL and others have started to adopt the term "collaborative economy" to emphasize the diversity of platforms and types of peer-to-peer-style services that have emerged. ShareNL defines the collaborative economy as “economic systems of decentralized networks and marketplaces that unlock the value of underused assets by matching needs and haves, in ways that bypass traditional institutions.” There is certainly overlap between this and the sharing economy, where the collaborative economy is broader, to include platforms like Ebay, and it emphasizes the transactional relationships between businesses, consumers, and peers. The sharing economy, on the other hand, is usually more narrowly focused on platforms that enable the shared use of commonly owned resources.

Making Sense of the Term "Sharing Economy"

While the city of Amsterdam succeeds in taking a practical stance about the sharing economy, it does not always distinguish between the organizational types of sharing initiatives that exist. In this way, the action plan brings to light an important issue that the sharing movement is currently grappling with. Like the plan explicitly states, there is no singular definition of "sharing economy." But there are certain categorical distinctions that must be made regarding the types of initiatives that fall under its purview. There is a huge difference between sharing initiatives that are organized as a non-profit, corporation, or cooperative. Their report does not delve into these critical distinctions.

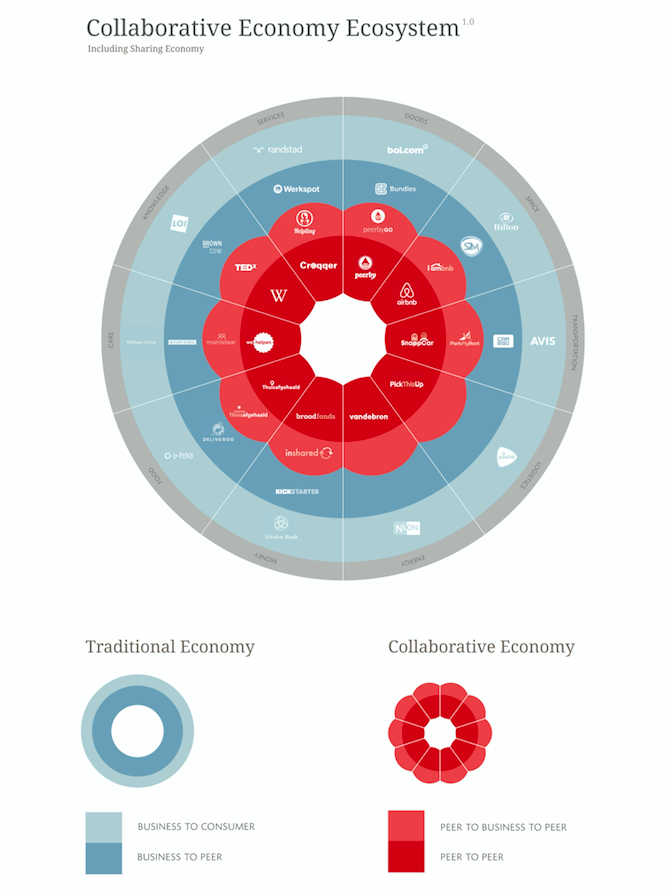

"Collaborative Economy Ecosystem" by shareNL is licensed under CC-BY-SA 4.0

Furthermore, the city includes shareNL's graphic on the collaborative economy ecosystem without pointing to these organizational differences. Airbnb is placed in the same "peer to peer" category as Wikipedia. The former is a purely a for-profit corporation, while the latter is a decentralized, self-governing community of individuals whose services and resources are managed by a non-profit entity. While Wikipedia is unquestionably a peer-to-peer knowledge platform, Airbnb is a business that takes a cut of profits as they connect suppliers of accommodations to occupants. Airbnb ought have been put in the "peer to business to peer" category.

On the same graph, Kickstarter is listed as part of the traditional economy in providing financial services. The company however, re-incorporated itself as a public benefit corporation last year. Though they are still a for-profit company, their renewed fiduciary commitment to consider the social impacts of their decisions is a pretty significant divergence from other traditional companies.

This graphic was developed by shareNL to purely highlight the transactional relationships between the peer-sourced supply and demand of goods and services. ShareNL defines the peer-to-peer category as encompassing the types of services where people meet face to face. But as a reader, it's disorienting to see these services categorized in this report this way because the action plan emphasizes the challenge that cities face in understanding whether a service is really about enabling sharing or is just a for-profit business operation. The graphic, by itself, does not make these distinctions or define what peer-to-peer means in the context of this report. Nor does the report as a whole delve into how an enterprise's organizational make-up determines their bottomline priorities.

Ultimately, we cannot count on for-profit companies to maximize positive social impact. Most of these "sharing economy" services' sole fiduciary obligation is to maximize profit, which means other objectives will likely be thrown by the wayside if they get in the way of that primary purpose. We can only really count on organizations that are specifically designed and chartered to meet the needs of their employees, customers, and communities to achieve positive social impact. This is why we need to pay attention to the organizational make-up of sharing enterprises. Questioning the governance structures of the enterprises and projects that are the building blocks of our future cities is a critical step towards building cities that are resilient, democratic, and sustainable — a true sharing city.

It's also important to be open-minded about the sharing economy: It's a growing sector that could likely subsume many goods and services industries. We can recognize that even the most controversial platforms have shown to have positive effects for communities. This report succeeds in framing this discussion in a way that recognizes such collective benefits and addresses the inevitable challenges. Yet it could have also addressed these fundamental questions about the institutions that comprise this movement.

Truth be told, we could all be much more critical in thinking about the objectives behind each initiative — that includes those of us at Shareable. During the early years of the budding sharing movement, the difference between corporate sharing services and sharing initiatives that were driven for and by the people who provided and used them, was a distinction that was rarely made. A true sharing economy is one in which enterprises are not singularly motivated by profit, and are democratic, equitable, and sustainable in and of themselves. If we're to truly advance the meaning and ethos of the sharing transformation, we need to be mindful about who the real stakeholders are behind any organization that claims to advance community sharing.

Go to the GEO front page

Add new comment