A Remembrance by Robert Bonazzi

Originally published in the The San Antonio Express-News

I

John Howard Griffin’s Black Like Me turns 50 on November 1, 2011.

Originally published in 1961, the classic has never been out of print in English, selling over 11 million copies in 14 languages. The 50th anniversary edition, reedited from Griffin’s original manuscript, was published this fall by Wings Press, an independent San Antonio imprint, in cloth and ebook formats, both including a Preface by Griffin’s friend, Studs Terkel. Black Like Me and many other Griffin ebook titles are available from Wings, all containing additional materials.

I cannot tell you how many people have reported that Black Like Me “changed my life.” While it is always gratifying to hear this remark and to feel the same about this courageously honest book, I must say that meeting Griffin in 1966 changed my life irrevocably, and it continued to evolve as we became friends.

II

In the late spring of 1966, I first met Griffin at his studio located in the countryside west of Mansfield, Texas, the town where he had been lynched in effigy six years earlier. I requested an interview for Latitudes, an independent literary journal I had started while doing graduate study at the University of Houston. Griffin had responded by return mail, inviting co-editor Dan Robertson and myself to visit.

Arriving downtown, we phoned, and his wife Elizabeth gave expert directions. We drove three miles through what were then called the Black and Mexican-American sections of the town—small wood frame homes and white-painted churches—then up the curving dirt driveway which led to the cinder block structure that Griffin used as his writing studio.

Since Dan and I had been involved in civil rights initiatives at our respective universities, we had read Black Like Me; but neither had read Griffin's novels, nor were we aware of his talents as photographer and musicologist. When we entered the cottage, which was thirty yards downhill from the main farm house, we noticed a kitchen, a darkroom, and a grand piano. We learned later that the studio had been Elizabeth and John Howard’s honeymoon cottage fifteen years earlier, where three of their four children had been raised.

But what astonished us were the magnificent black and white portraits that lined the bare white stucco walls—dozens of lively faces, most of them strangers to our eyes—peered back at us. We recognized the large images of Thomas Merton, the Trappist monk whose autobiography, The Seven Storey Mountain, we had read as Catholic teenagers. My New York Italian parents, who had dropped out of high school in order to work, had been wise enough to revere education and to provide books. They knew about Thomas Merton and Griffin was to hear that. He had recently been appointed by Abbot Dom James of the Abbey of Gethsemani in Kentucky (Thomas Merton’s home) to make a series of official portraits of the monk.

Then almost 46, Griffin looked younger, resembling a farmer rather than a writer, standing over six feet and weighing a robust 200 pounds. But he did not speak like a farmer or a native Texan, measuring his elegant language in a quiet tenor voice with a slight hint of a French accent. He wore dark sunglasses to protect his eyes from the glaring light of afternoon—eyes that had remained sensitive since recovering his sight, in January of 1957, after a decade of blindness. By evening, he would remove the glasses, revealing warm, hazel eyes. Initially, somewhat remote behind dark lenses, he moved about the room identifying "the faces of intelligence," as he called them.

"Merton is one of the most vital human beings I have ever known," he began in a rush, "and one of the most gifted, since he works splendidly in almost any medium: writing, painting, photography. During my last visit with him, it was like being in a room where lightning constantly struck. I realized as never before that this monk who long ago gave himself to monastic vows, gave up all worldly ambition and what we call 'freedom' is the most completely free and unfettered person I have ever encountered." Without intending it, Griffin had described himself, for the room was illuminated with his passionate enthusiasm.

He turned next to the portraits of Jacques Maritain, the French philosopher, whom he called his mentor. "Maritain is probably the greatest mind of our times. He wrote this magnificent Creative Intuition in Art and Poetry," he said, displaying the deluxe French edition like a holy grail, "which you must read, a tremendous book." We did not know Maritain's work and asked if it was in English translation. "Yes, I'll give you a paperback," he promised, but that was forgotten until a later visit.

As he continued along the walls, pointing out the few portraits we recognized— pianists Artur Rubinstein and Lili Kraus, blues legend Josh White and retired boxing champion Archie Moore—I saw that Griffin wore thick white socks covered by brown knitted house slippers, giving the impression of bulging feet on which he moved ever more cautiously.

Finally, after the tour had reduced him to hobbling, he disappeared into the restroom and returned rolling in a wheelchair. We learned that he had surgery on his feet. He lighted the first of many cigarettes, leaned back to take a deep pull on the filtered tip and smiled, as if to indicate he was ready to be interviewed. We began by asking about the influence of France, since he had first traveled there as a teenager in search of a classical education.

"Let me play you one of my greatest influences," he declared, switching on a tape recorder on the glass top table. A Mozart piano concerto leaped out and penetrated the sudden silencing of our voices.

We listened and wondered aloud: "You mean Mozart?"

"Of course, Mozart, the supreme genius; but I mean the pianist."

It was the French virtuoso Robert Casadesus, he informed us, playing with the Cleveland Orchestra under the baton of George Szell. "Robert, Casadesus, his wife Gaby, their entire musical family, really, were my greatest influence from France. It was Robert and the legendary teacher Nadia Boulanger who convinced me that my future as an aspiring composer—this when I was 26 and losing the last of my eyesight—should not be pursued. They felt that my true gifts would be revealed only after I had lost all sight and returned to America."

"They discouraged you from music?" I ventured.

He laughed heartily. "No, no, merely from composing, for I had learned all the rules but could breathe no life into the compositions." Had they not done so, he explained, he might have not traveled on to the Abbey of Solesmes, where he studied Gregorian Chant with the Benedictine monk-musicologists who encouraged his fascination for medieval music. It was there he had lost the last of his eyesight, and where his ears were opened to the eternal nature of the chants. Due to that experience, he was able to set his first novel, The Devil Rides Outside, in a French monastery and the surrounding village modeled after Solesmes.

"But they couldn't have known any of this," I countered.

"No one could have, least of all myself. But the point is that these two masters, Robert and Nadia, cared enough to be truthful, knowing that their example of dedication and integrity would lead me along my own path, which was most assuredly not as a composer."

There followed a charming monologue, rich with the excited memories of an unabashed Francophile. He spoke of his French literary masters, painters, composers and musicians; French art and architecture; the sciences, medicine, sociology and psychology; the joy of baking bread and the agony of making a subtle French meal.

He spoke about Pierre Reverdy, the French poet whose portrait was in that gallery, and we were surprised to learn that it was the first portrait that Griffin had ever made, just before he lost his sight completely. A longer version of this friendship appears in Scattered Shadows: A Memoir of Blindness and Vision.

Griffin even spoke of French existentialism, which Dan and I had been reading as students. While he did not care for Jean Paul Sartre's work—Dan and I did—all of us shared a deep appreciation for the work of Albert Camus. Griffin had translated parts of The Stranger as a step in relearning English, for it had taken years to "think in English rather than French." Then he declared that Maritain was "a Thomistic existentialist, if there is such a thing." We did not debate the point, nor could we have; but we expressed views concerning a few areas of disagreement. We loved jazz and the blues but Griffin did not. At that time, when Dan and I were 23, we knew these classic American forms far better than the European classics Griffin had mastered. He knew little about jazz, and he discoursed on how classical music had influenced his novels.

"I did not really set about learning how to write at all. Rather, I took musical forms and constructed my fiction on them. In The Devil Rides Outside, I used the forms of Beethoven's Opus 131 Quartet.” Since then, I have always translated musical forms into my work. I used the classical sonata form of Mozart in Street of the Seven Angels. In fact, I played Mozart continually during the writing of it, and anywhere the tone of the work did not coincide with the tone of the music, I changed the work." We were fascinated by this, because we had not read his fiction and had no idea how one might translate musical forms into novels.

Eventually we would read all his works and listen to the music upon which they were based; but the mystery of his intuitive process remained a mystery. Nonetheless, The Devil Rides Outside (1952) and Nuni (1956) remain two of the forgotten masterpieces of North American fiction. His third novel, a comic satire on censorship called Street of the Seven Angels, was published by Wings in 2003, forty years after it was completed.

That first electrifying visit lasted for eight hours. Along the way we were fortified by sandwiches and coffee, prepared by his wife Elizabeth and sent over on trays carted by their three children. But our visit had fatigued even the youthful interviewers and by ten that night we mustered enough sense to take our leave.

III

There would be many other visits after the Griffins had moved twenty miles north to Fort Worth later that year. In their sprawling rent house on West Biddison, he gave more interviews, introduced us to photographic techniques and played new interpretations of the classics. We brought along our wives and friends to meet the Griffin family. When my parents spent an afternoon there, Griffin took photos of the entire family, developing two remarkable portraits of my father. John Howard and Elizabeth were incredibly generous hosts, feeding the visitors and sending them home with gifts—inscribed books, matted prints, music tapes—which we treasured. He treated everyone as an equal and his humility was authentic. He had his heroes but never posed as one. In fact, he was very uncomfortable with fame. "I have had a life that I loathe, which is the public life. I have had to go in conscience, and also because I am under spiritual direction, and because we have had one racial crisis after another. I have been able to function in those crises, but all that time I have been away from my family and away from what my true vocation is." He was first and last an artist.

Our conversations and the 178 letters he wrote during our 15-year-friendship touched on the news of the day but always the primary focus was on the creative process and how it was essential to be in solitude and to give all to the good of the work. Toward my early efforts at poetry and fiction, when I was being published by the small press magazines of the day, he gave unstinting encouragement, and offered criticism that was invariably accurate and useful. Even though he was my elder by twenty-two years and was at the height of his creative powers and public recognition, never did he pull rank or become paternalistic.

"I feel something very warm and brotherly about you," he wrote in 1970. "And no matter how miserable and forlorn you feel" (I was going through a divorce then) "you are living important days in your life, at least in your creative life." He had often said that nothing is lost on the writer, or should not be, and he was right. Griffin taught us not to obsess on the misery of the moment but to focus on the spiritual horizon beyond mere ego. It was the sort of mentoring he accomplished without fanfare or pride, without acting as a mentor. He chose friendship and to express that sense of artistic brotherhood he embodied—never the mentor-acolyte relationship. Nonetheless he was a mentor to many of us, because we choose our mentors whether or not they choose us.

During a 1977 phone conversation he asked if I would assist Elizabeth with his literary papers. I was stunned, indicating that I would, but did not speak of it. I assumed that he would live a long life, even though he was suffering from diabetes and heart seizures, which did not stop him from giving lectures from a wheelchair.

After Griffin died on September 9, 1980, I traveled to Fort Worth to attend the funeral that was officiated by many of the priests who had been close friends. He was buried in the Holland family plot of the Mansfield cemetery, near his old friend and father-in-law, Clyde Parker Holland. After the service, we returned to the family home where Elizabeth mentioned my promise to help with Griffin’s literary papers. I had not realized she knew, but said that I would assist her whenever she was ready.

Two years later Elizabeth invited me to Fort Worth, and we began the work. She admitted to being unable to examine the many files that she said had been in a “mess” for several years before his death. I returned six months later to begin the work which took two years. During that period we were married and established a series from Latitudes Press (1966-2000), to bring out his unpublished works posthumously. We were aided immensely in this revival by Robert Ellsberg and Orbis Books, which published a new edition of Follow the Ecstasy (originally from Latitudes) in 1993 in US, UK and German editions. Orbis also published Griffin’s memoir, Scattered Shadows in 2004 and my Man in the Mirror: John Howard Griffin and the Story of Black Like Me in 1997.

Tragically, Elizabeth died in 2000 at age 64, and I closed down Latitudes Press. She had established The Griffin Estate in 1980, guided Griffin’s first posthumous book The Hermitage Journals into print (Andrews & McMeel, 1981), typed Follow the Ecstasy and Scattered Shadows and compiled the first Griffin bibliography. She had the strange experience of having been married to two writers—Griffin for 27 years and myself for almost 18 years—about which she maintained a delightfully ironic sense of humor.

About the Author

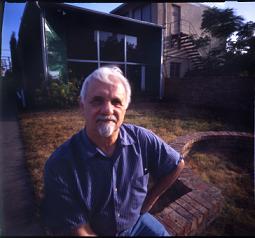

Born in New York City in 1942, Robert Bonazzi has also lived in Mexico City, San Francisco, Florida and several Texas cities. From 1966-2000, he edited and published over 100 titles under his Latitudes imprint. He lives in San Antonio and writes a column on poetry for the San Antonio Express-News and reviews for World Literature Today.

Born in New York City in 1942, Robert Bonazzi has also lived in Mexico City, San Francisco, Florida and several Texas cities. From 1966-2000, he edited and published over 100 titles under his Latitudes imprint. He lives in San Antonio and writes a column on poetry for the San Antonio Express-News and reviews for World Literature Today.

His major work on John Howard Griffin—Man in the Mirror: John Howard Griffin and the Story of Black Like Me (Orbis, 1997)—was praised by Jonathan Kozol, Studs Terkel, The Times of London, Chicago Tribune, Library Journal, National Catholic Reporter, Publishers Weekly, Booklist, The Catholic Worker, Texas Observer, Texas Books in Review and Multicultural Review.

As Executor for The Estate of John Howard Griffin, Bonazzi edited Griffin’s Black Like Me, Scattered Shadows: A Memoir of Blindness and Vision, Available Light: Exile in Mexico, Follow the Ecstasy: The Hermitage Years of Thomas Merton and Street of the Seven Angels.

His work on Griffin has appeared in The New York Times, Bloomsbury Review and The Historical Dictionary of Civil Rights. Bonazzi’s work has been published in over 200 publications—in France, Germany, Japan, South Korea, Canada, Mexico, Peru and the UK. He appears in the film documentary, Uncommon Vision: The Life and Times of John Howard Griffin (produced by Morgan Atkinson and aired on PBS).

He has published several volumes of poetry: The Scribbling Cure: Poems & Prose Poems (Pecan Grove, 2011) and Maestro of Solitude: Poems & Poetics (Wings, 2007) constitute a selected volume 1970-2010. Earlier books—Living the Borrowed Life (1974), Fictive Music: Prose Poems (1979) and Perpetual Texts (1986)

Citations

When citing this article, please use the following format:

Robert Bonazzi(2011). Encountering John Howard Griffin .

Grassroots Economic Organizing (GEO) Newsletter, Volume 2, Issue 11.

Add new comment