In 1975, leaders of New England’s food co-op community joined with socially-oriented investors affiliated with the Haymarket People’s Fund to unlock access to debt capital for the many food co-ops that were starting and expanding. Their experience led them to create the Cooperative Fund of New England (CFNE), a nonprofit Community Development Financial Institution (CDFI). CFNE exists to advance community-based, cooperative, and democratically owned enterprises with preference to those that serve low-income communities through: 1) provision of prompt financial assistance at reasonable rates; 2) provision of an investment opportunity that promotes socially responsible enterprise; and 3) development of a regional reservoir of business skills with which to assist and advise the above groups.

In 1975, leaders of New England’s food co-op community joined with socially-oriented investors affiliated with the Haymarket People’s Fund to unlock access to debt capital for the many food co-ops that were starting and expanding. Their experience led them to create the Cooperative Fund of New England (CFNE), a nonprofit Community Development Financial Institution (CDFI). CFNE exists to advance community-based, cooperative, and democratically owned enterprises with preference to those that serve low-income communities through: 1) provision of prompt financial assistance at reasonable rates; 2) provision of an investment opportunity that promotes socially responsible enterprise; and 3) development of a regional reservoir of business skills with which to assist and advise the above groups.

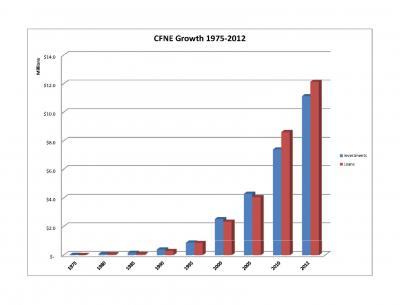

Now in its 38th year, CFNE has made over 630 loans worth $31 million to various types of co-ops, including worker-owned, producer-owned, grocery, and housing co-ops, as well as non-profits across New England and eastern upstate New York. By providing this financing, CFNE created or retained over 8,400 jobs and 4,400 affordable housing units, largely in the cooperative sector. Throughout its history, no investor in CFNE has lost any investment funds, and CFNE’s borrowers have repaid over 99% of its loan funds -- remarkable figures in the larger financial sector context.

Now in its 38th year, CFNE has made over 630 loans worth $31 million to various types of co-ops, including worker-owned, producer-owned, grocery, and housing co-ops, as well as non-profits across New England and eastern upstate New York. By providing this financing, CFNE created or retained over 8,400 jobs and 4,400 affordable housing units, largely in the cooperative sector. Throughout its history, no investor in CFNE has lost any investment funds, and CFNE’s borrowers have repaid over 99% of its loan funds -- remarkable figures in the larger financial sector context.

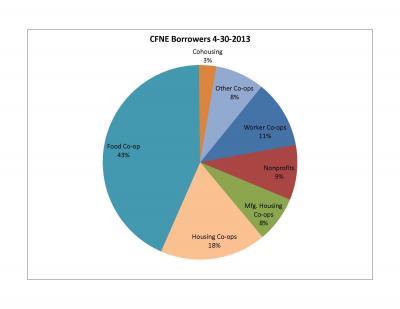

While a small amount of our loan dollars support worker co-ops (14% as of 4/30/13), they receive 23% of CFNE loans. This reflects the large number of relatively small loans made to start-up worker co-ops in our region, as opposed to the larger loans made to established food and housing co-ops.

Governance

CFNE’s governance was originally structured to maintain accountability from our nonprofit board to what, at the time, was our market: food co-ops. In the mid-1970’s, each New England state had a cooperatively-owned warehouse, serving the food co-ops in their territory. These warehouses appointed CFNE board members to represent co-ops in their state. While this was a democratic model for CFNE’s early years, it became untenable as CFNE grew. Over time, the board realized that they needed to place a higher premium on having specific skills on the board, including finance, nonprofit management, and capital development. While CFNE still strove to have board members from each state in its service area, it stepped back from having board members explicitly represent particular states.

CFNE’s governance was originally structured to maintain accountability from our nonprofit board to what, at the time, was our market: food co-ops. In the mid-1970’s, each New England state had a cooperatively-owned warehouse, serving the food co-ops in their territory. These warehouses appointed CFNE board members to represent co-ops in their state. While this was a democratic model for CFNE’s early years, it became untenable as CFNE grew. Over time, the board realized that they needed to place a higher premium on having specific skills on the board, including finance, nonprofit management, and capital development. While CFNE still strove to have board members from each state in its service area, it stepped back from having board members explicitly represent particular states.

As CFNE expanded from financing just food co-ops to include other co-op sectors and community-based nonprofits, it began maintaining board seats for sectoral diversity, including worker cooperators. At the end of 2012 we experienced board turnover with long-time worker co-op board members, LJ Taylor (Equal Exchange) and Margaret Atkinson (Green Mountain Spinnery), stepping down and Rebekah Hanlon (Green Valley Feast and the Valley Alliance of Worker Cooperatives) joining the board. We still have one board vacancy to fill, and hope to fill it with another worker co-op representative.

Recruiting qualified board members is further complicated by the fact that serving as a CFNE board member is no small task. CFNE has made a strategic decision to fund itself largely through the margin on its loans (the difference between the interest it charges and its cost of funds), rather than invest a lot of time on writing grants and soliciting donations. As a result, it has a small staff, requiring the board to volunteer significant time.

For a different governance model consider the Northcountry Cooperative Development Fund (NCDF), which was established a year after CFNE as a cooperatively owned and governed loan fund. To borrow from or invest in NCDF you must join the fund, purchasing an equity stake and receiving voting rights. Their co-op model has some challenges and opportunities as compared to CFNE’s 501c3 nonprofit model. Without placing too much emphasis on this, as there are a lot of consideration when evaluating loan fund structures and operations, CFNE can access additional government and foundation capital sources because of its nonprofit status, while NCDF can market itself as a cooperative and benefits from clear accountability to its market through direct elections for the board. Over its history, CFNE has periodically reexamined its structure to consider how we can best bring resources to cooperatives in an efficient manner.

Lending

CFNE is primarily a lending institution. It provides a range of financial products designed to meet co-ops’ specific needs, including both term loans and lines of credit. These products help co-ops buy inventory, equipment and real estate, and secure working capital for start-up, expansion, and seasonal cash flow needs. We offer competitive rates that vary depending on our cost of funds, the borrower’s risk profile, and the project’s social impact.

CFNE is primarily a lending institution. It provides a range of financial products designed to meet co-ops’ specific needs, including both term loans and lines of credit. These products help co-ops buy inventory, equipment and real estate, and secure working capital for start-up, expansion, and seasonal cash flow needs. We offer competitive rates that vary depending on our cost of funds, the borrower’s risk profile, and the project’s social impact.

While CFNE evaluates similar loan application criteria as other lenders, our familiarly with cooperative models allows us to find applicant strengths that conventional lenders overlook. Standard loan underwriting looks at: 1) the character of the applicant’s leadership; 2) the capacity of the applicant to repay the loan; 3) the applicant’s capitalization structure; 4) the current economic conditions affecting the applicant; and 5) the collateral available to secure a loan. Because of CFNE’s familiarity with cooperatives, we are able to apply these criteria more flexibly to our co-op applicants. For instance, if at all possible we do not require personal guarantees. We make creative arrangements such as having one food co-op guarantee a portion of another co-op’s loan through committing to buy their inventory in the event that the borrowing food co-op closes. In addition, we recognize the power of co-op associations and communities to strengthen individual cooperatives. While not all corners of New England have strong co-op support networks, we appreciate seeing co-ops participate in those that do exist.

CFNE’s loan agreements are significantly less restrictive and obtrusive for the borrower than most commercial loan contracts. The agreement is nevertheless a detailed and comprehensive one that is fully protective of the legal rights and financial solvency of CFNE. Reporting requirements include submission of quarterly financial statements on a timely basis. This allows CFNE to closely monitor the financial performance and organizational development of its borrowers. When quarterly financials or other information concern CFNE, it can reach out to the borrower with direct and referred technical assistance before problems grow too big to resolve.

In the past few years, CFNE has been experimenting in two areas to increase financial support to worker co-ops: new products to address collateral shortfalls, and building a partnership with the Small Business Administration.

Lending: Collateral Issues

CFNE recognizes that the lack of collateral is often a major barrier to worker co-ops securing financing, and has initiated three experimental products to address that issue, starting with the Cooperative Capital Fund of New England (CCF) in 2007. Through this affiliated loan fund, CFNE developed a pseudo-equity product whereby borrowers can access uncollateralized funds for a longer term than CFNE traditionally offered. CCF borrowers make interest-only payments until the loan term expires, at which point they repay the entire principal or replace the CCF loan with a less expensive CFNE loan.

While these funds resemble the uncollateralized aspects of equity, they differ in two significant ways. The first is that CCF gains no control or even governance participation in the investee co-op; the co-op members retain full power. Additionally, at the end of the term, the co-op owes the full amount of funds back to CCF. Because CCF loans are uncollateralized, and therefore riskier, CCF investors receive a higher return on their investment. This means that CCF funds cost more to the borrowing co-op than CFNE loans. Even though CCF has disbursed almost all of the $460,000 that it initially raised, that occurred slower than expected. It is not clear at this point whether CCF will raise more funds or not. Recently, CCF made a loan to Real Pickles in the context of their Direct Public Offering campaign. (To learn about Direct Public Offerings and the deal with Real Pickles, visit http://www.cuttingedgecapital.com/what-is-a-direct-public-offering/.) While this is not how CCF funds are generally used, it does demonstrate that different innovative financing mechanisms can work together.

In an effort to address the collateral issue in a lower cost way, last year the CFNE board set aside $750,000 of its loan capital as a discretionary pool for partially collateralized deals -- deals where the borrower has collateral to meet some of their debt needs, but not all. As these funds are part of CFNE’s normal loan capital, they come with no extra requirements or costs and, as such, are highly valuable. To date CFNE has committed about $200,000 of these funds.

Finally, CFNE has also developed innovative mechanisms to facilitate community investment in specific cooperatives. When Simple Diaper and Linen set out to convert their diaper laundry service from a sole proprietorship to a worker co-op, they had a lot of community support, but not a lot of collateral. Simple Diaper launched a community investment campaign whereby their supporters invested $12,000 in CFNE to collateralize CFNE’s loan to Simple Diaper. If the co-op stops paying its debts, CFNE will liquidate the community investment to cover the loan balance. If the business succeeds and repays the loan, CFNE will return these funds to the co-op. In other instances, individuals invested their funds in CFNE to collateralize a particular co-op. These investors receive interest payments from CFNE annually and, assuming all goes as planned with the business, are repaid their principal when the co-op no longer needs that collateral.

Lending: Small Business Administration

Following advocacy by CFNE, the US Federation of Worker Cooperatives, the National Cooperative Business Association and others, in 2011 the federal government’s Small Business Administration (SBA) revised their regulations to allow SBA resources to finance worker cooperatives [see Micha Josephy (2012). SBA Recognizes Worker Cooperatives as Small Businesses. Grassroots Economic Organizing (GEO) Newsletter, Volume 2, Issue 12. http://www.geo.coop/story/sba-recognizes-worker-cooperatives-small-businesses]. This decision has the potential not only to open the door for worker co-ops to access low-cost financing and technical assistance, but also to engage the SBA and its partners on how co-ops benefit the economy and our communities.

With the regulatory change and the creation of its intermediary lending pilot program, SBA awarded CFNE a $1 million long-term, low-cost loan to finance worker and producer co-ops in our region. This award helped to lower CFNE’s cost of funds, a benefit that CFNE passes directly to its borrowers by offering lower interest rates. As of this spring, CFNE has committed over 97% of these funds to twelve worker co-ops, one producer co-op, and one hybrid co-op. These borrowers include long-standing co-ops like Collective Copies, Green Mountain Spinnery, and Pelham Auto; recent conversions like Warrenstreet Architects, Simple Diaper and Linen and Artisan Beverage Cooperative; and start-ups like Catamount Solar, Local Sprouts, Fertile Underground, Dedham Artists Guild, hOurworld, and Toolbox for Education and Social Action. CFNE is currently looking at how we can use the SBA’s Community Advantage program to use government guarantees to help finance otherwise overly risky projects.

Investments

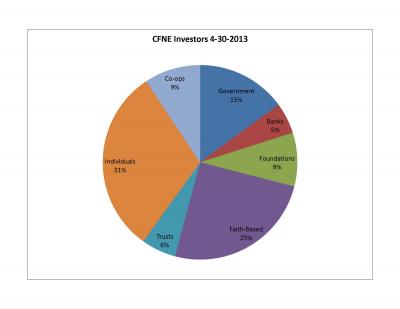

Where do CFNE’s funds come from? Mostly from individuals (31%) and faith-based institutions (25%). These sources are followed, in scale, by the SBA, foundations and co-ops (9% each). While the co-op investments are a small portion of our loan pool, they are arguably the most exciting as they demonstrate both co-op support for our work and a commitment from co-ops to invest in the sector. As the co-op movement in New England grows, we anticipate that co-op investments will become more quantitatively significant.

Where do CFNE’s funds come from? Mostly from individuals (31%) and faith-based institutions (25%). These sources are followed, in scale, by the SBA, foundations and co-ops (9% each). While the co-op investments are a small portion of our loan pool, they are arguably the most exciting as they demonstrate both co-op support for our work and a commitment from co-ops to invest in the sector. As the co-op movement in New England grows, we anticipate that co-op investments will become more quantitatively significant.

While the worker co-op investment in CFNE makes up only 3% of our total loan capital, worker co-ops have provided important leadership in this area. One particularly exciting innovation comes from our partnership with the Valley Alliance of Worker Cooperatives (VAWC), a regional association of ten worker co-ops in western Massachusetts and southern Vermont. VAWC’s members committed 5% of each co-ops’ pre-patronage surplus to the VAWC Co-operative Development Fund which is invested with CFNE. While this currently does not amount to a large fund, it is both symbolically important and builds a model and structure for greater co-op investment in the future. { From the Editor: See Adam Trott’s article in this issue for more information about this.}

Technical Assistance and Network Support

New England has a complicated technical assistance (TA) landscape for co-ops, including co-op associations, development centers, SBA affiliates and skilled individuals. CFNE provides direct TA support to co-ops primarily around our expertise -- applying for and borrowing loan funds. We walk applicants through the loan process, including sharing what we are looking for in application documents and reviewing their specific documents to identify strengths and weaknesses of the application – and, perhaps, of the applicant’s co-op. If there are significant weaknesses, we refer them to outside TA providers to address the issues. On occasion, CFNE has provided matching funds for technical assistance to worker co-ops.

Theoretically, CFNE’s financing mechanism could be leveraged to finance technical assistance, but timing proves difficult. Co-ops need the most technical assistance before opening for business, for training, a feasibility study, business planning, and marketing. But these early stage efforts are hard to finance as we cannot reasonably predict whether the co-op will succeed and repay the loan. In some cases, co-op organizers have reached agreements with technical assistance providers that state the co-op only owes TA fees in the event that the co-op earns sufficient revenue streams. NASCO Development has experience in this area in the co-op housing field.

We have also supported the development of co-op movement technical assistance capacity in both Greater Boston and western Massachusetts/southern Vermont, through co-op associations, including the aforementioned VAWC and Greater Boston’s WORC’N (Worker Owned and Run Cooperative Network), and the Boston Center for Community Ownership, an urban-oriented co-op development center that’s in formation. By providing limited start-up resources as well as energy to these groups, CFNE is helping to build local capacity in the worker co-op sector to support co-op development.

Looking Forward

One challenge that we’re facing is competition from conventional lenders. In this economy, where banks can borrow from the government at near zero interest levels, CFNE is facing unprecedented competition from banks to finance well-established, less risky co-ops. Historically having some of these safer loans in our portfolio has balanced the riskier start-ups and struggling co-ops who can’t find other affordable sources of debt. In the long run, losing these stronger co-ops as borrowers might threaten CFNE. Additionally, the “local business” brand is so strong that some local co-ops are choosing local banks over our regional co-op loan fund. Are these developments bad? If, after years of struggle, a co-op that we helped to start-up is stable enough to access conventional debt at cheaper rates, isn’t that a sign of our success?

Many of New England’s co-ops who can access conventional credit are now turning around and investing their surplus cash with us, facilitating investment in new, riskier co-ops. That’s an exciting trend and, as discussed earlier, certainly worth encouraging.

But looking at the bigger picture, the dilemma of how we approach strong, mature co-ops closely parallels an old discussion across the community economic development world -- are we trying to help underserved communities access the benefits of the existing economy or are we trying to create a new economy where everyone has adequate access? For CFNE, the question is: to what extent are we helping co-ops grow so they can access conventional financing and to what extent are we trying to be a permanent finance arm of the co-op sector? Maybe we should turn this question around to the co-op movement: how can we best continue to grow the co-op sector in New England and how can you help us accomplish that?

CFNE has demonstrated a lot of success over its life, financing many co-ops, providing ground-breaking instruments for co-ops to invest in co-op development, and supporting capacity building for technical assistance and co-op networks in New England. That said, the changing demand for financing from New England co-ops demands on-going innovation in CFNE, including experimenting with how to address collateral shortfalls, partnering with co-op associations, and reexamining the big question: “why are we here?” Ultimately, we hope these evolutions and innovations will help increase CFNE’s and the co-op sector’s size and relevance!

For more information about the cooperatives mentioned in this article please access the following urls:

Cooperative Fund of New England (www.coopfund.coop)

Equal Exchange (www.equalexchange.coop)

Green Mountain Spinnery (www.spinnery.com )

Green Valley Feast (www.valleygreenfeast.com )

Valley Alliance of Worker Cooperatives (www.valleyworker.org )

Northcountry Cooperative Development Fund (www.ncdf.coop )

Simple Diaper and Linen (www.simple.coop )

US Federation of Worker Cooperatives (www.usworker.coop )

National Cooperative Business Association (www.ncba.coop )

Small Business Administration (www.sba.gov )

Collective Copies (www.collectivecopies.com )

Pelham Auto (www.pelhamautoparts.com )

Warrenstreet Architects (www.warrenstreetarchitects.com )

Artisan Beverage Cooperative (www.artbev.coop )

Catamount Solar (www.catamountsolar.com )

Local Sprouts (www.localsprouts.coop )

Fertile Underground (www.fertileunderground.com )

Dedham Artists Guild (www.dedhamguild.com )

hOurworld (www.hourworld.org )

Toolbox for Education and Social Action (www.toolboxfored.org )

WORC’N (www.worcn.org )

BCCO (www.bcco.coop )

Citations

Micha Josephy (2013). The Cooperative Fund of New England. Grassroots Economic Organizing (GEO). https://geo.coop/story/cooperative-fund-new-england

Add new comment