[Author's note: In a recent panel discussion, Democracy Collaborative co-founder Gar Alperovitz called for dialogue and debate regarding the pros and cons of the Evergreen model. It's my hope that this blog series will catalyze just such a discussion. As most all the coverage of Evergreen so far has focused on the model's benefits, I focus here exclusively on what I see as a major drawback. If something I have to say strikes you as offensive or wrong-headed, please respond in the comments.]

I want to continue the discussion of the Evergreen Cooperatives that I started (or at least tried to start) with my last blog, What's Up With Evergreen?, but in order to do so I feel that I first need to lay a little philosophical groundwork, so bear with me.

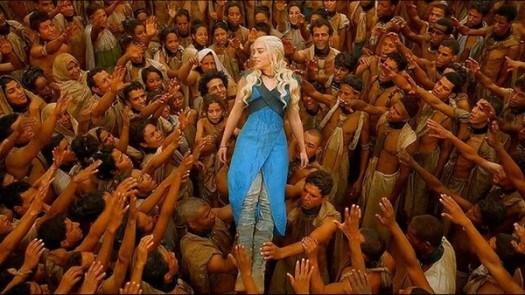

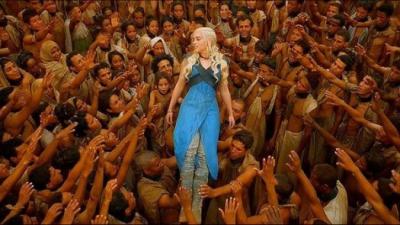

As an entry-point into our discussion, consider the term “white savior complex,” coined to describe a prevalent attitude and narrative around Western aid to African countries. The myth of the white savior holds that members of an oppressed group need a white person to save them and show them how to succeed. Thus, the oppressed are told they must turn to the very group that oppressed them in the first place for their salvation. This is a common trope in Hollywood movies as well as in international development. Dangerous Minds and Avatar are two text-book examples. If you think about it for a minute, I'm sure you can probably come up with a dozen more examples of your own.

As an entry-point into our discussion, consider the term “white savior complex,” coined to describe a prevalent attitude and narrative around Western aid to African countries. The myth of the white savior holds that members of an oppressed group need a white person to save them and show them how to succeed. Thus, the oppressed are told they must turn to the very group that oppressed them in the first place for their salvation. This is a common trope in Hollywood movies as well as in international development. Dangerous Minds and Avatar are two text-book examples. If you think about it for a minute, I'm sure you can probably come up with a dozen more examples of your own.

The white savior mentality is damaging on a number of fronts. For one, it denies the competence and agency of the people who are supposedly being helped – which is to say it is a patronizing attitude masquerading as compassion. This is simply adding insult to injury (albeit, with the best of intentions). White saviors fail to recognize that the plight of those whom they are trying to help is caused by the same discriminatory system that has placed them in an advantaged position to begin with. The problem is thus framed solely as a lack on the part of the oppressed, rather than as the natural outcome of an unjust system.

The white savior complex is ubiquitous in our society, as it offers a salve for white guilt while stroking the white ego by placing privileged people in the role of selfless hero. The abundance of white saviors in our society has, however, failed to result in much salvation for anyone but the white saviors themselves (and I freely cop to having been one myself). Ironically, projects to help poor people often turn out to be more lucrative for the people providing the help than for the people receiving it (see Non-Profit Industrial Complex).

The provocative – and probably unpopular – contention that I am going to make here is that Evergreen bears many hallmarks of the white savior complex. It is a project conceived by people who enjoy societal privilege in order to help an oppressed group. However well intentioned, it reinforces the idea that oppressed people need (mainly) white professionals to save them. While I assume the project planners had the best of intentions, it nonetheless seems undeniable that the Evergreen model has reproduced, at least in part, the dysfunctional dynamics of privilege that afflict our society.

Consider these statements from the recent report on Evergreen released by REDF:

Evergreen Cooperatives was established in 2009 as an incubator for worker-owned cooperatives in Cleveland, Ohio with support from the Cleveland Foundation, the City of Cleveland, and a group of local anchor institutions including the Cleveland Clinic, University Hospitals, and Case Western Reserve University. Additional assistance in designing the Evergreen model came from the Democracy Collaborative and the Ohio Employee Ownership Center. (pg. 2)

[...]

The businesses were chosen based on opportunities, the needs of the Anchor institutions, and the interests of funders, but without the industry expertise necessary to operate efficiently. (pg. 7) [emphasis added]

What is notably lacking here is any mention of the people the project is meant to benefit as having any agency at all. The project's designers are all relatively privileged members of society, occupying posts in government, in large institutions and in foundations. The people who are meant to benefit from the project are not similarly privileged. In fact, the report refers to potential worker-owners as the “target population," which is not a term that implies agency. So we have a situation where the privileged are coming to the rescue of the underprivileged – pretty much the definition of white savior complex.

And how bizarre is it that worker cooperatives were designed based on the needs and interests of institutions and funders, and not on the needs, interests, skills and abilities of the worker-owners? The report even sees fit to mention Evergreen's lack of industry expertise, but fails to mention the lack of worker input into (not to mention control over) the decisions of what and for whom to produce. Those have to be the two most important decisions a worker cooperative has to make, and yet by all accounts those decisions were made before the inclusion of worker-owners*.

Anyone who has followed the Evergreen story is aware that it's been a rather rocky road for the three cooperatives thus far (these two articles provide some in-depth background, for those who need to catch up). All of the businesses floundered for the first few years, and none of them is yet financially self-sustaining. Most of the problems that the businesses have faced were the result of poor planning by the organizers (i.e. the white saviors). Besides the lack of industry-expertise, mentioned above, the report highlights other failings by the organizers:

In hindsight, Evergreen executives acknowledge that the businesses should have had contract agreements in hand before starting the businesses, and that the product and service needs of the Anchor institutions needed to be better understood. (pg. 6)

An added problem for E2S is that, unlike in a union shop where workers come up through the trades, its workers mostly lacked construction expertise, and a lot of on-the-job training was required to get them up to speed. (pg 7)

Failing to provide accurate market projections and failing to understand the existing skills of workers...and these are just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to rookie mistakes by the professionals. In fact, from everything I've read about Evergreen, despite the rosy spin most of it has had, I am unable to escape the conclusion that Evergreen's organizers essentially convinced a bunch of poor people to take part in a poorly thought-out experiment that very nearly crashed and burned. And when that happened, who stepped in to save the day? Was it the workers, having some hard conversations and deciding on a course of action? No. It was Evergreen executives bringing in new management to fire workers and cut wages from, in some cases, $20 per hour to $9**.

The Evergreen executives failed to properly plan the businesses, over-hyped the possibilities and underplayed the risks to workers, and then when things went south, told the workers they were going to have to sacrifice to salvage the experiment that the professionals had initiated.

Evergreen Cooperative Laundry faced the steepest learning curve since it was the first business venture. At first, the workers were involved in all aspects of decision-making, which was difficult since most of them did not have experience in the laundry business and lacked some basic skills of financial management, including reading a profit and loss statement. When the new manager stepped in to streamline operations from the top down, the dramatic culture shift made it difficult to win the support and trust of all workers. However, as Ted Howard of the Democracy Collaborative said, “If you don’t make a profit, the experiment goes away.” Ultimately, the workers were persuaded that making the business profitable was in their interest as owners. (pg. 7-8)

Here we see the white savior complex in action. Blame for the project's difficulties is laid at the feet of the workers, despite the admitted failings of the executives, and the solution presented is for workers to just go along with what the people who know better (i.e. their white saviors) are telling them to do (even though it was those same people who led them astray to begin with). The thinly veiled insinuation here is that the worker-owners wouldn't even understand basic things – like the need for a business to make a profit – unless they had someone to explain it to them.

Maybe it was not the need to become profitable that was such a hard sell to the workers, but rather the ways being proposed to them to make that happen. Maybe the lack of trust was a result of being told they were owners and then having management decisions made without their input. Maybe they were suspicious of the people who had told them what a great idea all this was and how successfull they would be four years ago, and who were now telling them that they needed to take a 50%+ paycut or face unemployment. Maybe...

I've heard through the co-op grapevine that more than one of Evergreen's original worker-owners has left with a bad taste in their mouth. Some, I'm told, were downright traumatized by their experiences. My guess would be that the white savior complex has something to do with that. I think it's high time we talk about it openly.

*Another decision that appears to have been made without the input of worker-owners is the use of debt financing. From the report:

In a normal cooperative, worker-owners generally bring some capital to the table. However, given the target population and the process by which workers come to Evergreen, raising that kind of capital was not possible. Instead, all three businesses were entirely debt financed...While the debt funding allowed workers to own their full share of the businesses, it also created a significant debt burden that made it very difficult for these businesses to be profitable. Recently, some of the debt for E2S and ECL was converted to equity, and ECDF now owns Class B shares in these businesses.

Compare this with the Working World's model of non-extractive finance.

** While it's been reported that workers took massive pay reductions to save the businesses, it's never been mentioned whether or not any of the executives were asked to make similar financial sacrifices. I, for one, would like to know.

Add new comment