Co-op to Co-op Solutions to Grow Our Democratic Businesses

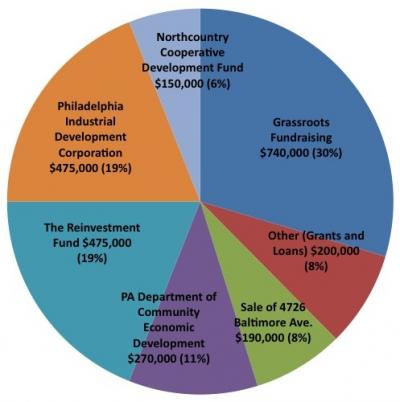

Mariposa Food Co-op is a consumer owned and member-worker run food co-op operating in the West Philadelphia neighborhood since 1971. After 41 years of being a members-only space, we opened our doors to the community in 2012, in a space five times that of our historic location. In total, our expansion effort racked up over $2.5 million in debt. Mariposa ramped up a massive fundraising effort to acquire our retail space of 2,600 sq ft, to restore the building to a greener version of its 1920s splendor, and to set up structures– from shelving and fridges, to point-of-sales and an administrative back-end, necessary to running a proper store. There are broadly applicable strategies about Mariposa's tremendous undertaking and unanticipated fundraising success; innovations that merit exploration despite Mariposa's atypical worker/ member structure.

Mariposa Food Co-op is a consumer owned and member-worker run food co-op operating in the West Philadelphia neighborhood since 1971. After 41 years of being a members-only space, we opened our doors to the community in 2012, in a space five times that of our historic location. In total, our expansion effort racked up over $2.5 million in debt. Mariposa ramped up a massive fundraising effort to acquire our retail space of 2,600 sq ft, to restore the building to a greener version of its 1920s splendor, and to set up structures– from shelving and fridges, to point-of-sales and an administrative back-end, necessary to running a proper store. There are broadly applicable strategies about Mariposa's tremendous undertaking and unanticipated fundraising success; innovations that merit exploration despite Mariposa's atypical worker/ member structure.

Our store grew directly out of a community of people coming together to address their own needs for specialty foods that were difficult to track down in retail spaces in the late 60s and early 70s. In addition to having a hard time acquiring items like soy milk or flax seeds back then, West Philly was in the early stages of what was to become a decades-long process of divestment, with grocery stores shutting down as in many inner cities throughout North America. Our roots in Mariposa have always been in our foundation as a worker-run and worker-owned operation. For ten years, Mariposa had no staff, but functioned on the pragmatic basis of members coming together to order food items, divvy them up, and distribute them as requested. In the 1980s staff were added on in an auxiliary capacity, to streamline certain operations, and assist with basic bookkeeping– but the vast number of “work hours” required to run our food co-op remained with unpaid members, who all did weekly and sometimes monthly tasks to keep things going. By the time that community demand exceeded our physical and operational capacity– lets say 2006– we already had a functioning staff collective coordinating the operations of the store, as a subset of a broader membership base (who all had workshifts, including cashiering) who continued to govern on a consensus-seeking basis. When the time had come to expend, Mariposa was able to draw on its dual aspects, of being both worker-run and consumer-owned, in order to piece together a robust set of fundraising benchmarks.

Our store grew directly out of a community of people coming together to address their own needs for specialty foods that were difficult to track down in retail spaces in the late 60s and early 70s. In addition to having a hard time acquiring items like soy milk or flax seeds back then, West Philly was in the early stages of what was to become a decades-long process of divestment, with grocery stores shutting down as in many inner cities throughout North America. Our roots in Mariposa have always been in our foundation as a worker-run and worker-owned operation. For ten years, Mariposa had no staff, but functioned on the pragmatic basis of members coming together to order food items, divvy them up, and distribute them as requested. In the 1980s staff were added on in an auxiliary capacity, to streamline certain operations, and assist with basic bookkeeping– but the vast number of “work hours” required to run our food co-op remained with unpaid members, who all did weekly and sometimes monthly tasks to keep things going. By the time that community demand exceeded our physical and operational capacity– lets say 2006– we already had a functioning staff collective coordinating the operations of the store, as a subset of a broader membership base (who all had workshifts, including cashiering) who continued to govern on a consensus-seeking basis. When the time had come to expend, Mariposa was able to draw on its dual aspects, of being both worker-run and consumer-owned, in order to piece together a robust set of fundraising benchmarks.

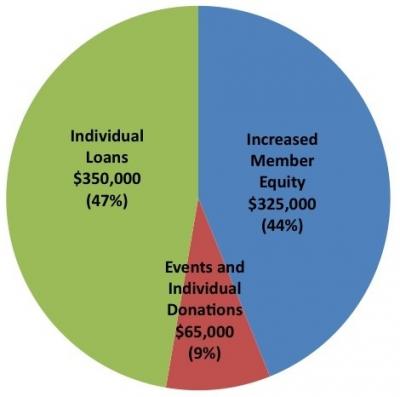

The success of our capital fundraising campaign is owed in part to the quirks of grants and donations that businesses can never anticipate in growing (such as a grant from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania for over a quarter million dollars), but it was unequivocally anchored by the dedicated support of our members, our community, and our allies in the co-op world. About 40% of our total project funding came from these areas– the largest slice of our fundraising pie– and that breaks down into three main categories:

The success of our capital fundraising campaign is owed in part to the quirks of grants and donations that businesses can never anticipate in growing (such as a grant from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania for over a quarter million dollars), but it was unequivocally anchored by the dedicated support of our members, our community, and our allies in the co-op world. About 40% of our total project funding came from these areas– the largest slice of our fundraising pie– and that breaks down into three main categories:

- Increased Equity from our own membership

- Many "small" Individual Loans- from members and other supporters

- Direct "institutional loans" from other co-ops and local businesses

Before explaining each category in brief, I want to mention a fourth area, which I think would serve smaller and entirely worker-owned businesses best– a capital campaign based on “community stakeholder” support. This I'll discuss later.

Increased “Equity” from our own membership

To become a member of Mariposa Food Co-op, the typical equity required is $200. We usually allow people to pay this in installments to make this more financially accessible, but for our capital campaign, we encouraged people to pay more– much more than the required amount, as an excess equity investment. Rather than treating this as a proper loan, we basically created a campaign where folks could put up to $8,000 or 10,000 as a zero-interest "loan" which they could get back in a matter of a week or two as needed. Our financial policies already laid out how we handle equity monies, so we did not need to create any additional paperwork to administer this.

To become a member of Mariposa Food Co-op, the typical equity required is $200. We usually allow people to pay this in installments to make this more financially accessible, but for our capital campaign, we encouraged people to pay more– much more than the required amount, as an excess equity investment. Rather than treating this as a proper loan, we basically created a campaign where folks could put up to $8,000 or 10,000 as a zero-interest "loan" which they could get back in a matter of a week or two as needed. Our financial policies already laid out how we handle equity monies, so we did not need to create any additional paperwork to administer this.

Having hundreds of people opt in to beefing up our campaign with anywhere from $600 to $6,000 added up to quite a bit of capital. As this pie chart demonstrates, it ultimately accounted for $325K total. That foundation of capital made it more attractive for institutional funders to lend us their money, since they saw evidence of community buy-in, and shared risk. They also knew that any debts that Mariposa took on would be prioritized such that institutional debts would be paid back before we paid off any member loans and equity. This provided additional security for them.

"Small" Individual Loans- from members and other supporters

It was important that we did not brand this as just member loans (although that is the language we mostly used internally). We wanted to be sure that friends and family of our members, potential future members, and other supportive parties could elect to invest in Mariposa, whether or not they were members themselves. Here we set a minimum requirement of $1,000 with no upper limit for loans. We offered terms of 5-10 years, with 3% interest.

Mariposa is located in a mixed-income neighborhood. Most of our members garner moderate incomes, and would struggle to come up with $1,000 of “disposable” or lendable funds in the form of a loan to our business– since this would be money they wouldn't see for at least 5 years. Nevertheless, by designing a campaign this way you can set benchmarks where a majority of lenders would be at the lower end of the scale, but just a few larger lenders can close a significant gap. For example, you could piece together 25 people at the $2,000 level, and another 5 people (or call them 5 “families”) offering a loan of $10K each, and you've got $50K + $50K or $100K.

Mariposa is located in a mixed-income neighborhood. Most of our members garner moderate incomes, and would struggle to come up with $1,000 of “disposable” or lendable funds in the form of a loan to our business– since this would be money they wouldn't see for at least 5 years. Nevertheless, by designing a campaign this way you can set benchmarks where a majority of lenders would be at the lower end of the scale, but just a few larger lenders can close a significant gap. For example, you could piece together 25 people at the $2,000 level, and another 5 people (or call them 5 “families”) offering a loan of $10K each, and you've got $50K + $50K or $100K.

In this way we built up something that felt almost like “crowd funding” except it was for interest-garnering loans, and not just donations (though we made it clear that we were always willing to accept donations). Since, we accepted loans from non-member investors I was able to convince my partner's parents to make a modest loan. They in turn convinced his brother and sister-in-law to also make a small loan. Our members, especially people in our staff collective and on our board and other committees– people who were highly committed– had an easy time persuading people in their lives that our vision for an expanded, worker-run, community-owned food co-op was a good investment. Our capital campaign offered better returns than interest from a high yield savings account would provide. Because this was a socially just cause it was not a hard sell.

"Institutional loans" from other co-ops

Many people involved in start-ups can speak to a yearning to get co-ops and “responsible businesses” in the habit of investing their reserves in growing our movement. At first folks at Mariposa were a little disappointed in how little interest there was from other co-ops in these kind of direct investments. We were talking about just a loan after all, not a donation. I quickly realized that the “fending for ourselves” attitude was really a product of the fact that co-ops and democratic workplaces have often felt that during expansion opportunities, they could only depend on their own reserves, and the willingness of banks and other lenders to take a “risk” on lending toward the cooperative enterprise.

One strategy that proved successful was to shift our ask, since the reluctance to part with internally accrued capital is understandable. We conducted an internal assessment and determined that even a short-term loan would help us close an essential gap in our profile. In light of this, we approached some of our friends in the co-op movement about supporting our campaign with a bridge loan, to lend us money for just a year. With this different ask, we did get support from another food co-op in the Mid-Atlantic. That bridge loan made a crucial difference in enabling us to begin construction while supporting our cashflow. We paid back that loan on schedule, after just one year, and in a much healthier place financially.

One strategy that proved successful was to shift our ask, since the reluctance to part with internally accrued capital is understandable. We conducted an internal assessment and determined that even a short-term loan would help us close an essential gap in our profile. In light of this, we approached some of our friends in the co-op movement about supporting our campaign with a bridge loan, to lend us money for just a year. With this different ask, we did get support from another food co-op in the Mid-Atlantic. That bridge loan made a crucial difference in enabling us to begin construction while supporting our cashflow. We paid back that loan on schedule, after just one year, and in a much healthier place financially.

To scale-up cooperative enterprises and democratic workplaces, we need to figure out how to really lean on and fuel growth by embracing principle six. As a movement we've got to put our capital to work in much smarter ways. Whether that is directly, or through loan funds, or some ramped up combination of the two, the fact that we understand the cooperative businesses model compels us to readily loan capital to other co-ops, without the same level of assumptions that traditional lenders espouse, about how “risky” co-ops are.

A new path

Part of what we had to achieve was getting enough start-up investment so that we could go to other lenders and prove that others were in on the risk; that we already had some capital amassed. Nobody wants to be the first investor, (least of all, traditional lenders) and that is perhaps where co-ops can play a special role. If we make a movement-wide campaign to committing early capital (especially to support co-ops in our sector, or in our local regions), it could possibly change the landscape so that lending institutions can jump in and fill in the outstanding gaps necessary to complete financing.

In this spirit, I'd like to sketch out a vision of what this could look like by drawing together the lessons outlined above from Mariposa Food Co-op's capital fundraising campaign.

One way of heating up the growth engine of democratic workplaces, would be to thread together a combination of the strategies that we used at Mariposa to create direct investment opportunities– from co-op to co-op and among local businesses. It is difficult to compare capital campaigns to one another given how varied the capital needs are from sector to sector and among different scales of operations. That said, what would it look like to kick-off capital campaigns by securing small loans (in the $5K-$10K range) from businesses local to your area?

One way of heating up the growth engine of democratic workplaces, would be to thread together a combination of the strategies that we used at Mariposa to create direct investment opportunities– from co-op to co-op and among local businesses. It is difficult to compare capital campaigns to one another given how varied the capital needs are from sector to sector and among different scales of operations. That said, what would it look like to kick-off capital campaigns by securing small loans (in the $5K-$10K range) from businesses local to your area?

In our own campaign in 2011, Mariposa received a loan on that order from Firehouse Bikes, the worker-owned/ worker-run collective, located just one block away from our own store. What I am envisioning, however is a situation almost the reverse of this. On the one hand, Mariposa is a member-owned food co-op, with a base of hundreds of members upon which to draw. Firehouse Bikes may only have 5–10 worker-owners, on the other hand; so what about businesses like Firehouse Bikes?

If a smaller worker co-op such as this was to take on an expansion they wouldn't have this vast member base to draw upon. But they are nonetheless located in a community which may value their services, their principles, the structure of a democratic workplace, and perhaps principles of localism or even sustainability and economic or social justice. What if we popularized a "community stakeholder" category– one where there was a structure for community level investment, from individuals, local enterprises, and co-op allies across the country. That could happen with interest incentives at rates competitive with financial institutions.

For individuals and households, it could also look something like allowing for 20% of the equity in the business to be available through community investment. If I didn't have the ability to make a medium-term loan to something like a Firehouse Bikes expansion, I might still be willing to offer $500 to $1,000 as an equity investment, even if it didn't accrue interest. What would the benefit be to me? As a local resident, I'd have the benefit of availing myself of the services of an expanded or otherwise improved local business (make my bike awesome! Expand your inventory so I can get a sweet ride! Expand your inventory to appeal to a broader swath of potential riders, helping to increase bike ridership with all the community benefits that entails... etc)

I remember talking to a few worker co-op experts about this at the National Worker Co-op Conference last June in Boston, and it seemed to them like a promising model. The idea that supporting and creating local industry not only through shopping but by investing capital in democratic businesses to enable them to stock the kind of inventory our communities need, and therefore be both supported during critical growth periods, and competitive (with traditional, capitalist bike shops for example).

So the question I'm posing to our movement to multiply and amplify democratic workplaces is, “how do we mimic consumer co-op models of 'member-investment' and 'member support' for worker co-ops?” Can we match the problem of having a smaller “membership base” and therefore a smaller potential for small “crowd sourced” loans and investments, with a principled strategy for co-op to co-op investment? To play to our strengths in order to relieve our movement of its most restrictive bottle-neck? Can we meet the capital problem with a capital solution??

Citations

Esteban Kelly (2013). From Crowd-Sourcing to Direct Investment: Co-op to Co-op Solutions to Grow Our Democratic Businesses. Grassroots Economic Organizing (GEO). https://geo.coop/story/crowd-sourcing-direct-investment

Add new comment