Livestream Clips

[Editor's note: below are two short clips from our last monthly livestream, in which Matt and Josh discuss the proposal for weighting hours in a worker co-op, for the purposes of surplus distribution, that Luis Razeto presents in chapter six of Cooperative Enterprise and Market Economy, which we published recently. For those who prefer to listen instead of read, we have also been creating an audiobook version with you can find on our SoundCloud and YouTube channels. Our next livestream will happen on Monday, August 14th, at 7 pm Eastern. We invite anyone who's interested in joining the discussion of these topics to join us on YouTube then.]

Transcript

Josh: So our big exciting news for this week was publishing. Chapter six of Cooperative Enterprise and Market Economy by Louis Razeto, translated by our own Mr. Matt:Noyes. And this chapter I found especially interesting because he goes about- well, he really talks about a number of different things in this, and actually what I think we're going to discuss mostly comes towards the end of the chapter. But one of the things he talks about is how a worker cooperative - an enterprise that's organized around labor - what makes sense as a way for it to count - or account for - people's labor inputs. And he puts forth this idea that maybe not everybody's labor should count hour-for-hour the same, which is just almost another way of stating a real basic thing from the economy, which is not everybody gets paid the same wage, not all jobs pay the same wage. But he has his kind of own way of getting into this and talking about it.

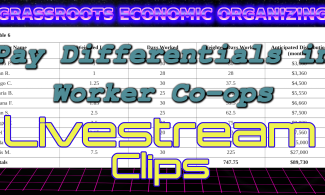

And Matt, so I was hoping - you're here, if you have gotten your wits about you, back from the radishes, and want to maybe give the breakdown of what Razeto's thing is here, and I'll actually put on the screen the article and the little chart so we can look at it while we're talking here. Let me do that.

Matt: Yeah, I think one line that stood out to me when I was translating it, that I enjoyed, was that somewhere in that passage he says, "Okay, but wait a minute. Isn't this argument that I'm making really just a way to justify inequality among members that's not based on economic rationality, but just reflects power differences." This is basically bringing the fundamental question to himself, about "is this just like some sort of rationalization of inequality?" And, you know, obviously his answer is no, there is a very strong economic logic to this, which is about understanding and tracking value flows related to labor, and about the idea that it's really a deeper idea of patronage. The idea is that your contributions, an individual's contributions to the cooperative, need to be recognized and remunerated in some form, in a way that is consistent with the principles of cooperativism, and is logical with the economic system, with the way cooperatives function.

And so his argument is that this is a way to do that. That the way that you go about this issue is by understanding that when people are contributing their labor, the labor that we do embodies not just a kind of standard abstract labor. All of us are working, but we do different things when we work, and the different things that we do can involve contributions of different factors. So I could bring a kind of administrative factor to it, I could bring a particular technical skill, I could bring whatever. Those are the things that need to be tracked and understood, so that the business, the co-operative, operates rationally - operates according to the economic rationality of the cooperative.

And so just the last thing I'll say about this, the key thing is he really separates this from the way that the market does things.

Transcript

Matt: And that distinction is is really important because it's also just psychologically in the standpoint of a cooperative member. I've seen it where people come into it thinking of it as pay. This is my pay, this is my wage, my salary. And it's really misleading because it's like, "No, this is the surplus. And we get to decide how much surplus to distribute. So we can set those rates at whatever rate we want to set them." It's a collective decision that gets made. So his question is kind of like what's- So it's a very political thing, always, what do you set the rate at? And I think it's political in cooperatives, too: it's a decision.

In his other book, How to Create a Solidarity Enterprise, when he talks about this question about pay rates he lays out three scenarios. One of them is this kind of weighted scenario, but another one is just equal pay, just flat pay rate. And he puts it out there as like "You have to decide. Which of these things do you want to do? And he has an argument for why he thinks the economic dynamics are going to be thrown off if you just do a flat pay rate. But he recognizes it's a political decision.

And I feel like in some co-ops, the solidarity that you get from a flat wage rate may be more important for the health and the continuity of the existence of the co-op than the economic rationality of a weighted system. It just may be the weighted system is going to look too much like inequality to people, and it may undermine the co-op, right? So I feel like it is fundamentally just a political decision.

One other thing I would note: one co-op here that I worked with, this landscaping co-op that I advised them a little, was they had an interesting thing which is they had a higher rate for stonework. Not meaning masonry or skilled stonework, but moving stuff, because picking up, loading and moving stone is really physically difficult and potentially you can get hurt, right? So they pay that at a higher rate. So that valuation doesn't necessarily have to be set by the market. There's also a way in which the co-op itself can do that.

Just one other thing to throw out there, that should be noted, is that he doesn't, I think, do enough with the C factor. The idea that you- like, in this chart.

Josh: Yeah, me too.

Matt: Yeah, in these charts he's looking at technical skill, these different things-.

Josh: Exactly, yes! Exactly. I was going to say.

Matt: Oh, well, let's come back to that then in a minute.

Josh: No, go for it. I'm glad that we're thinking the same way about this. Yeah, I looked at the list of functions, and I was going to point out he actually says in the paragraph up here - let me highlight it - in the process of establishing these weights, "the co-op could establish the valuations that the market habitually ignores. For example, contributions workers make to the societal integration of the group, that is the C factor contributions, which are undoubtedly of great importance and value in this type of enterprise." But then when we look down here, where is the C factor listed, right?

Matt: Right.

It's like that's not a function, even though he just said it's incredibly valuable, which it is from anybody who has experience. Like, it's probably the most important. And we had this at the worker co-op - former worker co-op - that I helped some friends start, was there was a guy there who was the peace-maker, and he was the like, "I can listen to anybody's stuff, and was really served that. And he didn't do the complicated stuff - he did all the what would be basic, simple labor here - but he served that particular purpose in the group dynamic. That was super important.

But it's like, we can say- so somebody who's a bookkeeper, somebody would say, "Well, what did you do to get those skills?" And they say, like, "Well, I went to school, and I did this, and I took that certification." Say, "well, what-" my friend, we'll call him John - "John, what did you do to get your skills?" Like, "Hmmm, well, let's see: I had an incredibly abusive upbringing and it made me very observant of people; and then I had to go through a bunch of dealing with my own stuff, and that made me very empathetic; and now I know it's like..." How do you value that? It's like,"...and I've been working on it for, you know, 35 years." But that doesn't even make the list, even for somebody like Razeto, who's thinking in those terms already. When he actually gets to putting numbers down, that goes out the window.

And I think one of the big reasons - and this is maybe a trap of him trying to work within the economics paradigm - is that anything that cannot be quantified is devalued by default. If it's easily quantifiable, that gets a value put on it, right? It gets a dollar sign put on it; and things that you can't really put a dollar sign on, they just- zero. They just kind of get a zero by default. And I think that kind of a problem he runs into, because a lot of these "soft skills," or things that - you know, the care work, as the feminist economists would have it - these kind of things, it's not easy to put a value on it. Or it's not like so simple as, "Okay, you paid how much to get your degree?" You know, these are very different kinds of things and that I think definitely need to be worked in. And I don't know if this kind of system is a good way to do that, or not. I mean, you mentioned that this is something that the DisCO, the Distributed Cooperatives, have worked on. I don't know, do you want to comment on how they've worked that, and if you have any insight.

Matt: Yeah, I mean it's really interesting. There's an interesting question - I don't know if it's the same process, ultimately, or a different process - but it is still a distribution of surplus questions. But what the DisCO folks do when they organize the distribution of the surplus, is they say we're going to distribute some of it for your livelihood work, which is the work that brings in revenue - and so these all of these things on the chart would of would apply to livelihood work, those are all sort of livelihood to work things, right? Although some of those things, administrative work and some of these other things, are not actually bringing in revenue. Those are those are just overhead, as they say. Those are costs to the cooperative, but nobody's paying you to do that. You just have to pay for it out of the revenue that you're getting from the actual work you do, right?

So there is a already some a distinction there, but in the DisCOs, it's just that when you distribute surplus, you distribute it for the livelihood work that brings in the money; for the care work, which is a pretty broad category - it can mean care in the more specific interpersonal, taking care of each other sense; it can mean a broader sense of, for example, some overhead administrative work ,or even support management work could conceivably be thought of as care work. The person who facilitates the regular meetings of the co-op members, and makes those be productive and healthy meetings: that seems a lot like care work to me.

Well anyway, they have this bucket of money that comes in from livelihood work: some of it goes to livelihood, some of it goes to a bucket for care - so the hours you spent during care work get paid - and then some of it goes to love work, which is the solidarity or pro bono work, or the contributions to the commons that the co-op does. So, like the landscaping co-op that I mentioned, Organa Gardens, their solidarity, their love work was, for example, tabling at a farmer's market in support of a political cause; not promoting themselves, but doing work that was in the general idea of promoting permaculture, for example, that would be for them important work to support. So that method, that's another way to think about the distribution. It seems to me it's not exactly the same as what was Razeto's doing here. It's not contradictory. The two things could be integrated.

Josh: Right.

Matt: I would I think "that stuff goes out the window," is a little too strong. But I think the point here is that what Razeto is trying to do is just explore - is come up with, 'here's how you could create this weighting system.' And I don't think he's intending this to be the exhaustive thing, and how it's going eeds to get what, what stuff needs to be packaged, in what way, in order to go to this person. She's doing a tremendous amount of administrative labor while she's in the field with me that I'm completely not doing. And if you took me out of that picture, you would not have anywhere near the impact on the farm, in its production. If you took her out, the thing collapses. So in that sense, I feel like it's rational to see that, and to recognize that, and recognize that the production process that we're involved in has those differences, and that they're very meaningful, and that therefore they should- in his framework, you should pay for the factors of production that are involved. You should value them, right? You recognize the value flows. Where's does the value come from, and do something to maintain it and sustain it. So that's the framework. So to me it's like if you think of it as pay rates, and pay rate differentials, then personally I think a flat rate is the way to go. So, like the Sustainable Economies Law Center: flat pay rate. You can be a lawyer, you can be someone sweeping up the office on your first day at work, answering phones, it doesn't matter. They just do a flat pay rate. That's a political decision that I'm pretty sympathetic to. But is it rational? Like, I don't know that that's particularly- to be done. This is just more like, "I need to establish that you could have a rating system, and it would make sense." but I do think it's a weakness - it would have been better if you addressed the question of, "how the the C factor things get counted in that?" And I'm not sure you couldn't put a dollar signs on those things, right? I mean-

Josh: Oh, yeah, yeah, yeah.

Matt: H.R. people get paid for the corrupt, rotten version of care work that they do.

Josh: Sure, yeah. You know, you could say, "Okay John, you spent an hour after that rough meeting patching things up with everybody, and getting everybody to feel okay. Alright, and your labor doing care work is weighted at 5.5," or whatever.

Matt: I mean, yeah, there are ways you could apply that. But when I was reading it, I had the same reaction: that I was just kind of like, "Well, wait a minute. What you just said, this great thing about we can have other standards, we can have other criteria here, and then you make a chart and they're not in there!" That's frustrating, it'd be nice to see them.

Josh: So my only other critique - and it's not really a critique so much, because as you said, Razeto was offering this as an example of a proof-of-concept - like, "you could do this," and I'm sure he is not set on any of the particular numbers involved. I still, however, think it's interesting looking at the numbers that he chose, just like looking at the particular list of skills that he chose and didn't choose. So I did just want to take a look at this.

So the weights that he comes up with range from 1 to 7.5, which in my understanding, that's basically a pay differential between the highest and lowest paid employee of 7.5, which sounds pretty good. And I definitely I remember reading years ago an interview with a large worker co-op in the US, with the CEO, and they were kind of bragging about the fact they only got paid ten times as much as the lowest paid member. So, you know, 7.5. And that's- I'm sure Mondragon, I think, is around there for many of their co-ops, for that kind of pay differential. And it looks pretty good, of course, in comparison to the traditional economy where we have large corporations with pay differentials of 360, 400-to-1, or whatever.

Still, this is something where I maybe just have a fundamental disagreement with a lot of people, or we just look at things differently - but to me, still, even this rate of 1 to 7.5 is not rational. It's not logical, because I think about what does it mean?

Well, so one thing I'll say - and this is just funny, right? So, Luis Razeto Migliaro wrote this book, and his hypothetical worker who gets paid the most in this co-op is "Luis M." I'm just saying. I thought it was funny.

So at any rate, Luis M in this example makes 7.5 times what Pedro and Juan make. So I read that as saying Louis can just come in on Monday, and then not come in for a week and a half, the rest of that work-week and then half of the next work-week - come in for half a day on Wednesday - and he'll get paid the same if as Pedro and Juan working five days a week, right? So if Pedro works seven and a half days - full days - which is a week and a half of a work-week, one and a half work-weeks, he gets paid the same as Louis working one day, right? Which to me does not connect.

I have a really hard time buying that okay, if we're both going to work 40 hours a week and you just get paid seven and a half times what I make, okay, that maybe sounds reasonable. But when I kind of switch the way I think about it, I'm like, "Wait a minute - that means literally you could make the same thing I make with only working one day every week and a half?" That doesn't sound right. So to me, I think maybe 1.85, 1.25, 1.5? I think our maximum pay differentials reasonably - like in a philosophically defensible way - would definitely not get above one to two, or one to three, maybe. I don't know, you can make an argument, but when it starts getting up to like this - to me, I think it's inconceivable that somebody can create as much value in a single day of work as somebody else in a week and a half, you know?

Matt: Okay, so right- I think the last thing you said it's helpful, I think, is that it's thinking about it in terms of creating value, as opposed to pay rates. You think about it as pay rates, it's just really locks you into this idea of wage rates where we're getting paid and those, we know, are based on capitalist exploitation. The reason the pay rates for workers are what they are is to generate surplus value. That's the whole point. Whereas in the co-op, everything belongs to all the workers, right? So in that sense, that dynamic is kind of off the table.

So the the question here is what are people bringing to the process? And then the question just becomes, is it conceivable that somebody-

So like the farm where I was working today: the farmer - is she bringing 7.5 times as much to the process of what we were doing today? Most of the time she was harvesting, I was harvesting. Her harvesting skills, I would put it certainly to twice as good as mine, or three times as good as mine. She just has more skill, and she knows how to harvest more plants, and she does it better. So she brings that skill to it. So you could make an argument that there's a that level.

But then, while she's there doing all this, she's simultaneously running through her head: the numbers, who needs to get what, what stuff needs to be packaged, in what way, in order to go to this person. She's doing a tremendous amount of administrative labor while she's in the field with me that I'm completely not doing. And if you took me out of that picture, you would not have anywhere near the impact on the farm, in its production. If you took her out, the thing collapses. So in that sense, I feel like it's rational to see that, and to recognize that, and recognize that the production process that we're involved in has those differences, and that they're very meaningful, and that therefore they should- in his framework, you should pay for the factors of production that are involved. You should value them, right?

You recognize the value flows. Where's does the value come from, and do something to maintain it and sustain it. So that's the framework. So to me it's like if you think of it as pay rates, and pay rate differentials, then personally I think a flat rate is the way to go. So, like the Sustainable Economies Law Center: flat pay rate. You can be a lawyer, you can be someone sweeping up the office on your first day at work, answering phones, it doesn't matter. They just do a flat pay rate. That's a political decision that I'm pretty sympathetic to. But is it rational? Like, I don't know that that's particularly-

Transcripts have been lightly edited for readability.

Citations

GEO Collective (2023). Discussing Labor Weighting in Worker Co-ops: Livestream Clips. Grassroots Economic Organizing (GEO). https://geo.coop/articles/discussing-labor-weighting-worker-co-ops

Add new comment