cross-posted from Shareable

For years, Montréal marked the cutting edge of green communities and economic democracy on the continent. The first community land trust in North America? The Milton Park limited equity coops near the Olmstead-designed Mount Royal Park. The top cooperative financial group in Canada? Desjardins founded over a century ago, part of a vibrant solidarity economy that's eight percent of Quebec's GDP. A charter of rights and responsibilities of residents, sort of a municipal Bill of Rights? Adopted citywide in 2006. A vibrant network of cooperatively run municipal markets showcasing Quebec farmers? Still going strong out of its Depression-era origins.

For years, Montréal marked the cutting edge of green communities and economic democracy on the continent. The first community land trust in North America? The Milton Park limited equity coops near the Olmstead-designed Mount Royal Park. The top cooperative financial group in Canada? Desjardins founded over a century ago, part of a vibrant solidarity economy that's eight percent of Quebec's GDP. A charter of rights and responsibilities of residents, sort of a municipal Bill of Rights? Adopted citywide in 2006. A vibrant network of cooperatively run municipal markets showcasing Quebec farmers? Still going strong out of its Depression-era origins.

Community gardeners planted their roots in Montréal soil in the 1970s and in the summer the city bursts with flowers and vegetable gardens crammed into strips liberated from asphalt and concrete.

But in this island city of 1.7 million, despite its famed green spaces and widely traveled bike lanes, a vibrant social economy is in a state of flux, buffeted by budget cuts, privatization threats and other challenges. At stake is the larger solidarity economy, which views collective well-being as nurtured through more democratic ownership and control of the economy, through worker coops, labor unions, credit unions or government-owned enterprises.

When I visited in July, the director of the city’s major urban environmental organization told me she worries that Montréal, once in the forefront of environmental initiatives, is falling behind just as the needs are greater with climate change. While Toronto is part of the C40 Climate Leadership Group, where is green Montréal? Véronique Fournier, director of the 19-year-old Centre d'écologie Urbaine de Montréal (Urban Ecology Center), mentioned one seemingly modest sign of the problem: “On the bike index, we’ve always been in the top 10 or 20 [cities]. But this year we went down and next year we might be kicked out.” On a larger scale, why isn’t public transit getting a fuller cut from the province’s new and worthy carbon trading system?

For their part, members of “social” and “solidarity” economy groups described grappling with both provincial budget cuts and centralization; they face layoffs and an erosion of localism, a central value of the movements. On a wider level, years of provincial budget cuts to universities — $70 million in 2015-16 alone — plus threats to long-established pensions have hit Montréal hard, inspiring numerous street protests.

In late March, Québec began cutting budget to regional support for the social and solidarity economy, though Chantier de l'économie sociale, a Montréal-based coalition of nonprofit and coop networks, did not receive cuts. The province is also cutting and consolidating grassroots community development organizations, known as Corporations de développement économique communautaire (CDEC). With union members and community residents on their boards, CDECs were key agents of local development, supplying communities with grants and loans from the government, and “solidarity funds” of unions and credit unions. Nonprofits, small businesses and coops have long relied on CDECs for credit and investment in a financial world that typically neglects these interests. Now, far fewer community groups or public agencies will provide this vital service. CDECs continue to exist but are limited mainly to their “workforce development” arms, supporting people excluded from the labor market.

These cutbacks are particularly worrying as both Montréal and Québec have long been beacons of solidarity economics, especially since the 2007 US Social Forum popularized their initiatives. In the 1980s, when global companies shuttered factories, leaving soaring unemployment in their wake, unions began investing more in the local economy. Quebec’s two largest unions created pension funds which, in exchange for a tax credit to those investing in them, are required to invest a majority of their funds in businesses and social economy enterprises rooted in the province. This made them the largest private investors in Quebec.

These cutbacks are particularly worrying as both Montréal and Québec have long been beacons of solidarity economics, especially since the 2007 US Social Forum popularized their initiatives. In the 1980s, when global companies shuttered factories, leaving soaring unemployment in their wake, unions began investing more in the local economy. Quebec’s two largest unions created pension funds which, in exchange for a tax credit to those investing in them, are required to invest a majority of their funds in businesses and social economy enterprises rooted in the province. This made them the largest private investors in Quebec.

When cooperatives launched in the Great Depression faded elsewhere in Canada, they grew in Quebec with the support of both the government and unions.

Support for the “social economy” took hold in the 1990s, when a Montréal-based women's movement and others supported the development of the Chantier de l'économie sociale. The movement’s founders hoped this social economy would “replace a liberal market economy with a socially oriented one,” as scholars Jean-Marc Fontan and Eric Shragge wrote in one of the first academic looks at the movement. This eventually lead to the Chantier winning heavily subsidized universal day care and the best teacher-child ratios in the country, removing this caring profession from the vagaries of the market. These and other wins were part of a larger discussion and drive to improve the working and living conditions for people in the region through the social economy.

Despite much social progress, cuts are made even while the provincial government issued a statement in support of the social economy model.

“There is less support in the public sphere. Structures we used to rely on don’t exist anymore,” says Stephanie Guico, 32, a Montréal native and coop consultant working in New York City. “This year’s [budget] agreement came with strings attached – recentralization into the federation to enact local programs with reduced funds and smaller staff.”

Sharing, Québec-style

The Québec model of a government and civil society supported economy that is more democratic and egalitarian remains visible even as budget cuts sweep through the province. Worker-owned forestry enterprises in the North, paramedic coops and the sheer number of worker-owners place Québec in the company of other coop strongholds like the Basque region of Spain and Emilia-Romagna in Northern Italy. In fact, there are over 7,000 coops and nonprofit businesses in Quebec employing over 150,000 people and generating over $17 billion in sales. Many of the coops have roots in the Great Depression and the Quebecois nationalist drive for local control against businesses owned by Anglophones – aided by rise of then social-democratic Parti Quebecois starting in the 1970s. While Saskatchewan’s coop stronghold, also rooted in the Great Depression, faltered, Quebec’s coop sector was re-energized by movements and public investment.

Workers control these enterprises on a one-person, one-vote basis. By provincial law, coops also reinvest in other coops. If coops close or are sold, they must dedicate their accumulated surplus or “indivisible reserves” to coop development. Any “profit” from the sale does not get divided among current worker-owners, leaving a legacy for the future from the generations that built the coop. This helps ensure the coops operate for the broader public interest, not the individual profit of the worker owners.

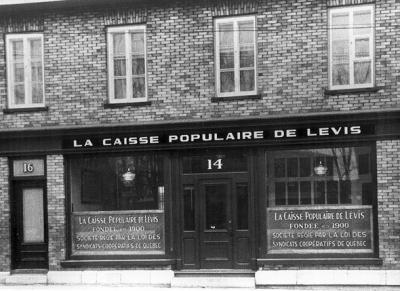

The province is also home to a massive network of credit unions, Desjardins Caisse Populaire, or “people’s banks” that together make up one of the largest financial institutions in Canada. Unlike American credit unions, the caisse populaire are free to give large business loans as well as provide consumer banking services. They are economic powerhouses built by French Canadians to enrich their region during an era when Anglophone Canadians dominated finance and investment. While most Quebecois do not take advantage of the ownership their deposits give them over the operation of the caisse, they at least nominally have democratic control of the major financial institutions that provide vital support to the local economy. Last year, Bloomberg listed Québec’s credit union system as the second strongest financial institution in the world.

The province is also home to a massive network of credit unions, Desjardins Caisse Populaire, or “people’s banks” that together make up one of the largest financial institutions in Canada. Unlike American credit unions, the caisse populaire are free to give large business loans as well as provide consumer banking services. They are economic powerhouses built by French Canadians to enrich their region during an era when Anglophone Canadians dominated finance and investment. While most Quebecois do not take advantage of the ownership their deposits give them over the operation of the caisse, they at least nominally have democratic control of the major financial institutions that provide vital support to the local economy. Last year, Bloomberg listed Québec’s credit union system as the second strongest financial institution in the world.

Quebec’s “solidarity economy” also features diverse unions, which help maintain living wages even when unemployment is high – and whose substantial investments in provincial businesses insure they have a say in economic development; the public ownership of the huge electrical utility Hydro Quebec, which earns billions for the provincial budget — $2.5 billion in 2014 — and Canada's national health system. These kinds of public ownership and locally controlled investment are key strategies for enriching and stabilizing local economies and meeting community needs against the whims of footloose companies and profit-taking in key sectors.

Community Development for the Little Guys

To understand why it matters that CDECs’ involvement in small business development is curtailed, I visited Reso – Regroupement economique et social du Sud-Oest – a CDEC in a gentrifying neighborhood on the south side of Montréal. It is known as a successful CDEC, helping job seekers and new and established businesses, including nonprofits, with loans and grants. When I visit in mid-July, it is a shell of packing boxes and empty offices; due to the cutbacks, Reso is consolidating, but will continue its job development work on the building’s first floor. Ironically, Reso intends to rent the empty floor out to small businesses as a coworking space.

Sitting in a sun-filled conference room, Reso’s director of investment, Marc Beausoleil, cataloged the losses. “We lost the Local Investment Fund ($1 million), the local Solidarity Fund ($500,000 from the union FDQ), and the other very important tool we lost was grants for social economy enterprises” such as a local theater and daycare. “That’s quite a loss for us…Humanly, it was a tough time. We lost 30 people here.”

Beausoleil said the impacts reach far beyond his group: “The objective was clear – to save $14 million in Quebec... All the work done by community groups, unions and labor people who were invested in their neighborhood were put aside.” In Montréal alone, according to Beausoleil, the cutbacks mean that “Now there will be only six economic organizations [helping communities], when there were 18."

Indeed, in a joint interview, Milder Villegas, director of the union-founded fund Fílatíon, and Bernard Ndour, director of Desjardins Caisee d’economie solidaire, wondered how they would fund the range of local, smaller enterprises, for-profit or nonprofit, with CDECs removed from the picture. Quebec Investments, a government agency with a branch focused on coops and nonprofits formed within the past decade, may face the same problem.

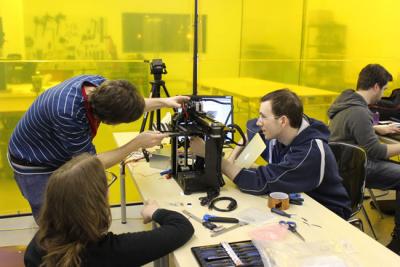

Lambert Le and his new nonprofit makerspace, Helios, was one of the social economy enterprises that benefited from Reso’s help after being turned down elsewhere. The brainchild of five recent graduates of Montréal universities, Helios provides, for a monthly membership fee, a range of woodworking and metalworking tools and 3-D printers for artists, industrial designers, hobbyists and surprisingly, families. The grads were frustrated because they had lost access to their universities’ facilities and realized they could create something to share with others thirsty for tools.

“It’s like a gym membership. It doesn’t make sense for people to use their tools in their living room!” said Le, 26.

After being turned down by a downtown development agency, “I met with Reso and they were very interested.” After advising that the entrepreneurs lower their income expectations in their business plan, Reso gave them a $15,000 loan and helped with marketing to gain them exposure. Now Helios is operating in the black.

After being turned down by a downtown development agency, “I met with Reso and they were very interested.” After advising that the entrepreneurs lower their income expectations in their business plan, Reso gave them a $15,000 loan and helped with marketing to gain them exposure. Now Helios is operating in the black.

Beausoleil fears that without their important intermediary role, less investment will flow to small businesses and nonprofit startups like Helios and more investment will end up in the hands of big enterprises that are less in need of credit, and have few connections to the community. “It’s really an attack on our model, very decentralized, bottom up, near the community and businesses. It’s how we worked for 30 years and in a couple of months it’s all broken.”

Yet, even as Montréal scales back its social economy, the city is hosting an international conference on the topic in 2016. “At the same time they were trashing the model, they [in the city government] were happy to say we will have a conference on the social economy in two years, when the network was destroyed,” said Charles Gagnon, Beausoleil’s deputy at Reso.

At Reso, his boss said, they are determined to keep supporting local development. “We will come back to the roots and go back to the community and ask, ‘what do you want us to do with fewer tools but the same purpose. We’ll have an impact on the borough.”

Uneasy Alliance: The Social Economy and Social Movements

As Montréal's social economy shrinks and reshapes itself, the transition is exposing the sometimes uneasy alliance between emerging social economy initiatives, and traditional social movements, such as labor.

A prime example is the Chantier, a network of networks founded in the late 1990s. The group encompasses a broad terrain: Workforce integration enterprises which work with those who are marginally incorporated into the labor force, CDECs, day care centers, home care services, and the Reseau network of worker coops.

Beatrice Alain, Chantier’s project manager for international affairs, said the group strives to bring some unity to a diverse array of social economy initiatives: “Food coops, worker coops, a nonprofit: they are all different sectors but they are always trying to create a more equitable sustainable economy.” The Chantier advocates for these sectors at the provincial level, generates supportive services that meet common needs, and boasts a knowledge exchange, RELIESS.

But this sprawling network faced some skepticism from the start: the large forestry and paramedic networks of worker coops never joined; unions eventually accepted its existence and took seats on the board with the understanding that the Chantier’s members, whether nonprofits or coops, would not take over work currently done by unionized public employees.

Also getting a jaundiced eye from some activists are Chantier’s member “workforce development” enterprises which employ marginal workers while providing social support during their job hunt. One activist dismissed them as “running what felt like sweatshops under the social economy mandate.” Many are run by “experts,” without a democratic voice for client communities, often immigrants or people of color. As Guico put it, “The decolonizing of the social economy [around ethnicity] that is happening [in the United States] isn’t happening there.” Beatrice Alain of the Chantier strongly disagreed with this characterization saying, "Worker integration enterprises offer new immigrants job-training but also language training and help them understand and adapt to the society ...into which they have arrived. They are recognized by the government as a result of their economic and social impact."

“There’s been a heavy reliance on government support as opposed to the US...We had a government that was so supporting that we forgot how to do it ourselves."

If the recent cuts to this sector are any indication, the Chantier’s days of swimming in provincial money may be numbered. Only about one-fifth of its budget comes from foundations, and most of the rest from the government (around 40%), said Jean-Marc Fontan, a scholar at Universite de Montréal and longtime researcher on the subject. As one critic from within the social economy movement explained, “There’s been a heavy reliance on government support as opposed to the US where it is more bootstrap. We had a government that was so supporting that we forgot how to do it ourselves." All these challenges can’t be helped by Chantier’s August appointment of a high profile politician and investment banker with Morgan Stanley Capital International to serve as its new director. Called “the darling of the sovereignists” by local newspapers, Jean-Martin Aussant is a telegenic Quebec nationalist who left the teetering sovereignist party, Parti Quebecois, in 2011 to form his own. The Chantier asserts that it is the key voice of its member groups in dealing with the provincial government – so Aussant will be trusted with the keys to many kingdoms, including those who are critical of the impact of international finance on building an egalitarian economy.

“There is a subset of the social economy that uses the language of nation and uplift,” said Guico. “But there is a new social economy – land trusts, [community] gardens, businesses that aren’t exclusively for profit. The startups of the social economy wouldn’t identify with the older institutions and the narrative of nation-building.”

But Isabel Faubert Mailloux of the worker coop network Reseau believes there is reason for hope, at least for her sector. The province is supporting more conversions of traditional businesses to coops. Unions are growing more interested in worker ownership, as are youth. “Young people want to make a business, but in a socially responsive way. That’s good for the worker coop model.”

Building a Solidarity City

Projet Montréal offers another reason for optimism. It is the “opposition” party in the city, with green-socialist politics focused on making the city more egalitarian, livable and sustainable. It controls only two boroughs but has 19 of the 65 seats in the city council (there are another 38 councilors at the borough level). The party champions greening streets, pulling up concrete for gardens as they did in the alleys of one of the boroughs they control, and affordable cooperative or nonprofit housing.

“Green alleys, we did four last year in my borough,” said Craig Sauvé, a city councilman with the party. “They used to be utility alleys. They closed it off for parking. They had to go door-to-door getting people to sign on. We’d get the department of public works to dig up the asphalt.”

This “traffic calming” measure is radical (and controversial) because it puts pressure on car owners, reducing available parking spots. Montréal is a car-centric city, with an estimated 1.5 cars for every person; it is one of the ways environmentalists feel they are lagging. Despite this, the two boroughs re-elected the party.

The party’s economic strategy is to make the city more livable so businesses and people will want to contribute to its vitality – what Projet Montréal councilor Christine Gosselin calls “grassroots economics.” While supporting the social economy, the party uses its powers in the boroughs it controls to generate jobs. In the eastern part of the Plateau neighborhood, Projet Montréal is holding public hearings to develop an underused industrial strip into an employment hub. The party is also promoting the idea of incorporating renewable energy as a requirement in new housing developments.

That Montréal can keep generating new and even radical parties that are founts of innovation stems from Québec’s political structure, which allows residents to be a member of multiple parties at once – of Projet Montréal and PQ or the Liberal Party, or all of the above. In a province where the “national question” of Quebec sovereignty or the dominance of the French language can drown out other politics, this rule enables local alliances.

Author Benjamin Barber has argued that “cities can save the world,” by regenerating democracy so humankind can take on the ills of climate change and footloose global corporations not bound by location or loyalty.

Will Montréal be one of those cities? Projet Montréal would certainly say yes.

“Climate change – we know it’s going to affect everyone,” says Projet Montréal Councilor Gosselin. The goal needs to be nothing less than “adapting the city to a post-individual paradigm.”

Professor Fontan is not so sure about Montréal’s leadership. “At first, I thought there could be like a virus within the social economy that would grow and spread. After 20 or 30 years, I had an observation: I met such interesting people, they had values, they have ideas and a revolutionary spirit, why didn’t they succeed?” The government and society, Fontan said, only became more market-oriented.

Despite Montréal's state of social economy flux, the city remains an important part of the movement, hosting the Global Social Economy Forum in 2016. The city still has a social economy liaison, and gives points for contracts with social economy enterprises. The summit provides another chance for the sector to make its case. “We say here we want a plural economy: public, private and social. This is what we’d like to see in Montréal,” says the liaison, Johanne Lavoie. With the summit, more people will see “the social economy is contributing to the wealth of the city in a different way. It will change their mindset.”

Still, in an era of budget cuts, one must ask how far cost cutting and profit-seeking will encroach on the foothold of cooperation and community control built over decades.

(originally published under a CC BY 3.0 license)

Go to the GEO front page

Add new comment